The Lady Vanishes

To fully appreciate the uniqueness of Dutch portraiture, it is helpful to consider it in the context of portraiture of the Italian Renaissance, both of which are products of very specific cultural expectations and norms. First of all, Italian Renaissance portraits of women were not trying to be truthful copies of the sitter, but of the idealized woman. Portraits of women greatly differed from those of men, who were painted as individuals and generally emphasized their social, political, or professional role. The women, on the other hand, were seen as objects of display, and their portraits were meant to advertise the wealth and virtues of husband or family; this was achieved by hanging the trappings of idealized beauty onto the frame of the female subject. Lorenzo the Magnificent described this ideal beauty as a woman “of an attractive and ideal height; the tone of her skin, white but not pale, fresh but not glowing; her demeanor was grave but not proud, sweet and pleasing, without frivolity or fear. Her eyes were lively and her gaze restrained, without trace of pride or meanness; her body was so well proportioned, that among other women she appeared dignified…in walking and dancing…and in all her movements she was elegant and attractive; her hands were the most beautiful that Nature could create. She dressed in those fashions which suited a noble and gentle lady…’ *

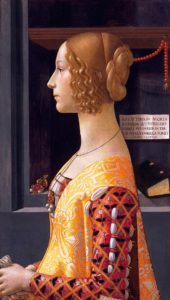

Well – I think that we can agree that these demands would be pretty difficult for a real flesh-and – blood woman to live up to, and of course, few did. Instead, the artists did a bit of Renaissance ‘airbrushing’. As Patricia Simons argues in her essay “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture”, the decision to portray female figures in profile stemmed from ‘psychological decisions’. She states that “women were painted in profile to appear chaste and display modesty. The female profile tended to be rendered with an elongated neck, unsubstantial body, and flattened facial features. The averted eyes and lack of sexual attributes Because costume and jewelry conveyed such a mass of information, artists often focused as much on the wardrobe as the woman, who was considered to be a piece of property herself.d, plucked eyebrows, blond hair, fair skin, rosy cheeks, ruby lips, white teeth, dark eyes, and The vision of virtuousness, specifically modesty, humility, piety, obedience, and chastity, was achieved by depicting the beautiful sitter in profile with an adverted gaze.” **

Below is an example of this idealized image: Alesso Baldovinetti’s profile Portrait of a Lady in Yellow, National Gallery, London, (ca 1465)

To make the link between poets and the idealized female image, I would like to introduce you to (if you haven’t already met) one of our most extolled Renaissance ladies: Laura de Noves, made famous by her most ardent admirer, Petrarch (1304-1374). Her beauties were the subject of his many sonnets, written in the Italian sonnet form in her praise (often called ‘The Petrarchan Sonnet’). Her beauty was not only immortalized in verse, but also in portraiture, such as the well-known portrait displayed in the Laurentian Library in Florence:

Petrarch’s Laura: Anonymous (ca ), In the Laurentian Library, Florence (date unknown).

The collection of Italian verses, Rime in vita e morte di Madonna Laura (after 1327), translated into English as Petrarch’s Sonnets, were inspired by Petrarch’s unrequited passion for Laura. Sonnet 227 (in English translation by A. S. Kline) demonstrates how dominant the idea was of representing woman via an idealized image of an untouchable and ethereal beauty. In reading through the sonnet 227, see if you can find Laura!

Breeze, blowing that blonde curling hair,

stirring it, and being softly stirred in turn,

scattering that sweet gold about, then

gathering it, in a lovely knot of curls again,

you linger around bright eyes whose loving sting

pierces me so, till I feel it and weep,

and I wander searching for my treasure,

like a creature that often shies and kicks:

now I seem to find her, now I realise

she’s far away, now I’m comforted, now despair,

now longing for her, now truly seeing her.

Happy air, remain here with your

living rays: and you, clear running stream,

why can’t I exchange my path for yours?

Although the sonnet is not about the portrait of Laura de Novis, it adopts the same type of representation of the woman that were characteristic of renaissance portraiture in general: a distancing from the real woman behind the image and focussing instead on the idealized instead: in particular the ‘blond curls’ that grace her brow! But that’s it! The rest of the poem is focussed on the lover’s frustration and his appeal to ‘co-conspirators’, ie, the breeze and a ‘clear running stream’ to act as his ‘proxies’.

When I first read this sonnet, I was reminded of a similar poem by Robert Herrick (1591-1674), whose love lyric is addressed not to the beauties of his beloved but praises the effect of the breeze on her clothing and, in turn, its effect on her admirer (ie: it’s all about him). This poem creates a similar distance from the real woman behind the image and I’m including it here to give a good idea of the pervasiveness of the representation of woman through the idealized ‘fog’ of love poetry that matches that of painting. This poem was written about 300 years after Petrarch’s, but coincides with the period of the Dutch Golden Age – highlighting even more strongly the break that Dutch portraiture made from prevalent attitudes of the period:

“Upon Julia’s Clothes”, (Robert Herrick, 1591-1674)

Whenas in silks my Julia goes,

Then, then (methinks) how sweetly flows

That liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes, and see

That brave vibration each way free,

O how that glittering taketh me!

Aside from that brilliant coinage ‘liquifaction’, which you just have to love, we are still left with no sense of the lady herself. She becomes an ethereal being, present only in her beautiful garments. Alas! The Lady Vanishes!***

One might expect that portraiture in the Dutch Golden Age, because of its focus on the domestics and the ‘down-to-earth’ and ‘every-day’, would be much more honest in its representation; it seems that nothing could be further from the truth. In The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (1987), Simon Schama describes the Dutch mentality of the period as one of tension between piety and morality, on the one hand, and unprecedented prosperity and materialism on the other, all placed within the framework of the domestic. One study, “The Portrayal of Women in Dutch Art of the Dutch Golden Age: Courtship, Marriage and Old Age” (Gerard Koot)**** examines the role of women in this religious and materialistic environment. In following the work of Wayne Franits, Koot suggests that ‘the study of domesticity in Dutch art must inevitably be about women, particularly women in relatively comfortable economic circumstances, since they were pictured as being involved in sewing, spinning, the supervision of servants and the care of children.’ In order to understand the well-known Dutch paintings that feature domestic scenes,’ all of which present ‘idealized expectations of how men wished women to behave in a patriarchal society’.

As represented in art, we find these expectations within “images of domestic virtue” in seventeenth century Dutch Paintings … ‘works of art that represent women in a variety of wholesome situations, most of which pertain to the home and the family.” and that these paintings were ‘carriers of cultural significance and ‘plausible realities’ that represented a culture that privileged men and devalued women.*****

So, even though we see a difference between the ethereal Italianate portraits and the more ‘honest’ and ‘down-to-earth’ representations in Dutch portraits, both are painted, not in their own ‘reality’, but in the realities of a patriarchal world and its cultural symbols.

Below is an excellent example of this kind of portrait: Adrianna Buuck, by Pieter Pourbus. The painting was commissioned as part of a pair on the occasion of the wedding of Jacquemine Buuck and Jan van Eyewerve, who was an alderman and wealthy resident of Brugges. Note the family coat of arms just above her left shoulder, carried by a cupid, and the image of a Statehouse to her right. Note also the gloves that she carries: they are not the fancy wedding gloves that were the norm for wedding pictures, but look to be worn and above all, practical. (See an interesting comment on gloves in 17th century portraits: https://www.renaissancefestival.com/forums)

PETER POURBUS: ‘Portrait of Jacquemyne Buuck’, 1551

Context of its display: positioned opposite her husband, on either side of the entrance in the Groeningemuseum, Brugge.

The following poem by Edgar De Perron (1899-1940), perfectly captures the tensions that Simon Schama describes (see above): between economic success and piety, and the woman’s role in symbolizing both.

‘Adriana de Buuck’

(Edgar Du Perron, 1899-1940)

A sixteenth-century lady, not yet twenty;

the brow is narrow but young and smooth, and round

it the hair is piously combed back and brown,

with a fine gauze cap set on it lightly.

The figure stands unmoving, all in black, and where,

slipping out from the fur, the sleeves impress

some life with their warm crimson on that funereal dress,

the hands lie stiff together; little colour there.

And calm, too calm is this young woman’s face. We may

guess at a fire those soft red lips betray,

deep down within those staring eyes suppressed.

A starved emotion, by a brutish lord,

church-going, languid gesture, modest words,

unworthy of the Virgin, as if by steel oppressed.

(Collected Works, Vol. I, 1955. Translated by Tanis Guest)

In this ekphrastic poem, Du Perron sketches the claustrophobic life that he discovers in every aspect of Pourbus’ painting. The lady is not idealized in the Italianate manner, with golden hair light on her brow, but plain brown hair that is simply and ‘piously’ combed back’ and crowned by a simple white cap, a familiar image of Dutch portraiture. The young wife’s plight is noted in her ‘stiff hands’, piously folded, Yet, in spite of this generic image of Dutch ‘domestic sensibility’ and piety, Du Perron finds a touch of humanity in the painting that defiantly peaks out from the ‘funereal clothes’, betraying the real warmth that is suppressed beneath the weight of her status and her pious Calvinism ( ‘church-going’). Both poem and painting are, indeed, honest studies in the cultural norms of a period – ones that, just as Renaissance portraiture, contained the woman within the framework of domestic duty and symbols of her husband’s success.

In stark contrast to the almost dire image of a ‘maiden trapped’ by the trappings of marriage, one painting of Frans Hals turns the tables on the expected depiction of wealthy couples and gives us an honest glance into their life. Of course, the painting is filled with recognizable symbols, as was the custom, but these symbols are not of wealth or stature or piety, but of a happy and fruitful union.

Frans Hals, Married Couple in a Garden, (ca 1622), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Subject: This portrait probably commemorates the wedding of Isaac Abrahamsz Massa and Beatrix van der Laen in 1622. Both were wealthy, educated members of the Dutch Republic’s elite: she a regent’s daughter; he a merchant and diplomat with Russian connections. This happy, smiling pair sits comfortably close to each other. According to the curatorial notes at the Rijksmuseum, ‘posing a couple together in this way was highly unusual at the time. It may have been prompted by the sitters’ friendship with the painter and the occasion for the commission – their marriage in April 1622. The painting thus contains references to love and devotion, such as the garden of love at right, and at left an eryngium thistle, known in Dutch as ‘mannentrouw’, or male fidelity’.

In an excellent editorial in the Guardian (August 2003), on the exhibition of this painting in 2003, Jonathan Jones, highlights the many ways in which Hals’ painting forges new ground in portraiture and signals a refreshing departure from the calvinist norms of representing matrimony. I would like to finish this chapter by giving Jones the last word on the Hals painting and its significance:

According to Jones, the distinguishing features of the painting are; “sexy, comic, unruly, this is a rollicking masterpiece. It does not do anything correctly. It laughs at stiffness and propriety, and Beatrix and Isaac are clearly in on the joke. Instead of sitting formally indoors, they sprawl under a tree. Instead of posing carefully, they let their clothes and bodies hang loose and baggy. Most of all, instead of paying respectful attention to her husband, Beatrix, resting her arm matily on his shoulder, grins knowingly at us. Beatrix is the central presence. Her left hand, over her groin and pointing down at the fertile earth, is virtually dead centre. And you can’t avoid that teasing face. She is the spirit of the painting, and it, too, is a smirk, a happy giggle. Isaac, for one, could not be happier. He makes no attempt to hide his girth. They both wear voluminous, dark clothes that seem to inflate them, to expand their presence in flowing black silks. His neat beard and white glove feminise him; her ringed, proprietorial right hand masculinises her. They enthusiastically trespass on one another’s territory. This convergence, an alliance far more than formal, is the painting’s meaning. Isaac and Beatrix, in their matching ambiguous silks, are so at ease that they seem to blend under the tree. In the distance, more couples court in a formal (but not too formal) garden, where a fountain pours water as if it were wine. They are all doing the natural thing, under a fresh, mobile sky, where two birds fly together.

If this is a painting praising union, it is also, in its form, a poem to change, development, the unpredictable. By grouping his subjects so closely, so roughly and, crucially, to one unbalanced side of the picture, by making them almost too big for the scene (they reduce everything else to Bruegelian miniature detail with their rude presence), Hals eradicates stillness and creates a sense of breath, air, gusto.” (The Guardian, August 2003)

Next Entry: Friday, 2 February (really). This entry will be a continuation of this present section on portraiture (Rembrandt and Hals).

Footnotes:

*http://www.academia.edu/11978486/Women_in_Frames_the_gaze_the_eye_the_profile_in_Renaissance_portraiture_1988

** Christiansen, Weppelmann, and Rubin. “Understanding Renaissance Portraiture.” The Renaissance Portrait: From Donnatello to Bellini, by Keith Christiansen, Stefan Weppelmann and Patrician Lee Rubin, 4. New York:Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.)

*** A small digression: The sense of distancing that is created by idealized images will be very familiar to you: consider ‘My love is like a red, red rose’ (Burns), ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ (Shakespeare), ‘She walks in beauty like the night’ (Byron), not to mention metaphors like ‘teeth like pearls’, ‘eyes like diamonds’, ‘cheeks like apples’, ‘flaxen hair’. Imagine a portrait that brings all of these qualities together and you come up with quite a frightening image. In fact, this has been done and I am trying to find it).

**** An excellent essay on the topic is ‘The Portrayal of Women in Dutch Art of the Dutch Golden Age: Courtship, Marriage and Old Age’, Gerard Koot, History Department, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, 2015

***** Wayne E. Franits, Paragons of Virtue: Women and

Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art (1993).