This chapter offers a journey into the world that gave rise to the mysterious ‘Lady of Shallot’ and her many illustrators. To understand why the Pre-Raphaelites produced such a wide variety of responses to the lady, who transgressed by leaving her mirror to look out upon the real world, it’s helpful to understand how the Victorians viewed the woman and her place in their world, a world marked by huge advances in science and technology, prefaced by an Industrial revolution (1750-1840), work houses, child-labour, extreme poverty and slums. (Your favourite Dickens’ novel will give you some of the best insights into this developing world and its effect on daily lives.) In the Victorian period (1840-1901), the explosion of new ideas (for example, on education, philosophy, religion), not to mention the rise of Darwinism, had a profound effect on every day life. But this ‘enlightenment’ had little effect on the social structures which defined Victorian womanhood, and prevailing ideas about womanhood can be found throughout the art and literary movements of the time. Two of the most interesting (and opposing) ideas of Victorian womanhood are the woman as ‘The Angel in the House’ and the ‘Femme Fatale’ and these offered a wealth of images to both artists and writers.

The Angel in the House

The ideal woman was expected to be devoted to home and family, as well as being submissive to her husband. She was charming, a graceful and elegant representative of her husband’s success, and, most importantly, was pure. The ‘angel’ was laid out in the poem by Coventry Patmore, ‘The Angel in the House’:

Man must be pleased; but him to please

Is woman’s pleasure; down the gulf

Of his condoled necessities

She casts her best, she flings herself.

How often flings for nought, and yokes

Her heart to an icicle or whim,

Whose each impatient word provokes

Another, not from her, but him;

While she, too gentle even to force

His penitence by kind replies,

Waits by, expecting his remorse,

With pardon in her pitying eyes;

And if he once, by shame oppress’d,

A comfortable word confers,

She leans and weeps against his breast,

And seems to think the sin was hers;

Or any eye to see her charms,

At any time, she’s still his wife,

Dearly devoted to his arms;

She loves with love that cannot tire;

And when, ah woe, she loves alone,

Through passionate duty love springs higher,

As grass grows taller round a stone.”

― Coventry Patmore

Our modern sensibilities might lead us to say that ‘these are fighting words!” (Indeed, Virginia Woolf, in an essay titled ‘The Angel in the House’, declared that the woman writer’s duty was to kill this phantom that restricted female creativity.) The whole notion of the ‘angel’ put the woman in an impossible situation as she was “to fulfil herself in the ‘instinctive’ arts of child rearing, domestic pursuits, and spiritual comfort”. Intellectual women were deemed unfeminine because a woman’s “heart” was valued over her “mind,” the mind being associated with the masculine, but at the same time, she was expected to educate her children. She was expected to be a pillar of moral strength and virtue, but at the same time she was portrayed as delicate and weak, prone to fainting and illness.

It’s clear that being the ‘angel in the House’ was a tough call. And woman who departed from these rules, was not regarded as ‘free-spirited’, as we might say today, but rather as a ‘fallen woman’, one who no longer has any stake in society. There were many ‘Advice Books’, offering rules of behaviour for young women to help them avoid the pitfalls and temptations of the world, including ample warnings of what would happen if they stepped over the line.

The evocative painting by William Holan Hunt, The Awakening Conscience, (1853) depicts the moment when such a ‘fallen woman’ suddenly sees the error of her ways and leaves the embrace of her lover.

The tragedy of the painting is that, according to the ‘advice books’, there is no doubt that she has thrown her life away and it is not likely that she will ever be redeemed. A fallen women even risked being put into asylums for being ‘mentally unstable’.

Going hand in hand with this notion of the woman as victim, an image that was explored in the pre-Raphaelite arts and poetry of the period. The notion of woman as tragic figure was famously expressed by the American poet, Edgar Allen Poe, when he stated that ‘the death of a beautiful woman is undoubtedly the most poetical topic in the world’.

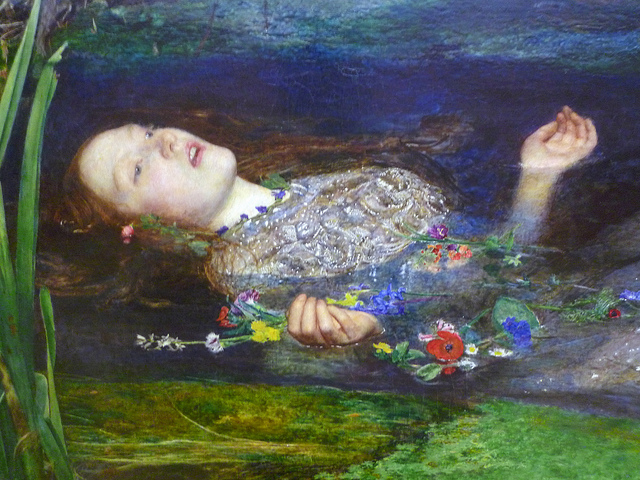

The pre-Raphaelite painter, John Everett Millais, reflects this sentiment in a painted counterpart to Poe’s ‘maxim’. The painting is a depiction of Act IV, Scene vii, in which Ophelia, driven out of her mind when her father is murdered by Hamlet, falls into a stream and drowns:

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up;

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element; but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

Ophelia, (1851-52), Tate London

The Femme Fatale

The Femme Fatale offers a different view of the Victorian woman, and this lady is not to be trifled with! She is a symbol of emancipation and a much-needed antidote to Byron’s ‘Don Juan’: she is fatale to men. According to Henk van Os:

“The seductress and the femme fatale are two essentially different species . At first glance, it may seem that these two types of woman resemble each other, but look more closely and you’ll find a fundamental distinction. For the seductress, her sexuality and voluptuousness are ends in themselves. Not so the femme fatale…she uses her feminine attractions t lure men to their destruction…. and ultimately their death’ .

This idea of the femme fatale developed in the second half of the 19th century amidst social changes that threatened the old values and mores. Women were becoming more emancipated and were fighting for their rightful place in society. As van Os further points out:

‘the place of the artist in society was also changing and this, together with growing middle class, led men and women to look for new forms of entertainment. They longed to escape the dull daily routine into a fantasy world filled with high tragedy and stirring symbolism. What could have proved more satisfying in such a period than the femme fatale? She made spicy, aroused and excited her viewers, yet at the same time, served as a warning. So the old stories were unpacked …tales from mythology or the Bible, the adventures of Medea, Circe, the Sirens, Judith and Solome were told anew. But this time the women weren’t heroines nor models of female chastity and piety. Artists …were to give the women a new role: they became seductive vamps plotting the downfall of the male.’ 1

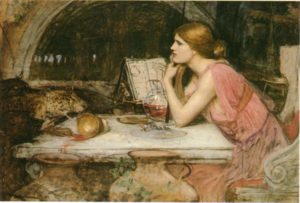

One of the favourite characters from mythology is Circe, daughter of the sun god Helios, who had the curious habit of changing men into pigs.

As Waterhouse represents her, with her loosened hair and exposed breast, eyes half-closed and offering the cup of magic potion to Ulysses, she is the epitome of the femme fatale, preparing to destroy her next victim (notice the unfortunate pig lying at her feet). In her dominance, she commands the entire picture plane (notice Ulysses barely visible, reflected in the mirror behind Circe).

*oil on canvas

*148 x 92 cm

*1891

As pointed out on the Victorian Web, ‘Waterhouse indicates that Circe is in control by positioning her above the eye of the observer; her seat is raised up on a step and she tilts her chin upward so that we must look up into her eyes as she looks down. In this way, Waterhouse manipulates her posture to place her in a position of superiority. In addition, Circe’s background indicates power in that the shapes which frame her (the mirror and the arms of her chair) create the effect of a throne.’

It is interesting that Waterhouse depicted Circe in two very opposing manners, in fact, reflecting the two images of womanhood that were most popular, this time, the softer, more domestic figure.

Circe by John William Waterhouse, 1849-1917

‘Instead of sitting on a throne, Circe occupies a much more domestic position at a table, surrounded by urns. She is informally leaning forward with a book open by her side, as if she is working on her spells in privacy. Her jaw is still strong, yet her lighter hair, soft pink robes and downward gaze onto the table produce a less intimidating effect. In this pose, chin in hand, Circe appears to be quietly contemplating something in the manner of many Pre-Raphaelite ladies’. (Victorian Web)

Finally, let’s have a look at the mysterious femme fatale as depicted in the ballad by John Keats, ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, a poem that inspired the contemporary Pre-Raphaelites in their depiction of the ‘Femme Fatale’. In this poem, where a wandering knight is lured into an ‘elfin grot’ … a perfect subject for the arts’ obsession with this ‘dangerous lady’:

La Belle Dame Sans Merci

John Keats, 1795 – 1821

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms,

Alone and palely loitering?

The sedge has wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms!

So haggard and so woe-begone?

The squirrel’s granary is full,

And the harvest’s done.

I see a lily on thy brow

With anguish moist and fever dew,

And on thy cheeks a fading rose

Fast withereth too.

I met a lady in the meads,

Full beautiful—a faery’s child,

Her hair was long, her foot was light,

And her eyes were wild.

I made a garland for her head,

And bracelets too, and fragrant zone;

She look’d at me as she did love,

And made sweet moan.

I set her on my pacing steed,

And nothing else saw all day long,

For sidelong would she bend, and sing

A faery’s song.

She found me roots of relish sweet,

And honey wild, and manna dew,

And sure in language strange she said—

“I love thee true.”

She took me to her elfin grot,

And there she wept, and sigh’d fill sore,

And there I shut her wild wild eyes

With kisses four.

And there she lulled me asleep,

And there I dream’d—Ah! woe betide!

The latest dream I ever dream’d

On the cold hill’s side.

I saw pale kings and princes too,

Pale warriors, death-pale were they all;

They cried—“La Belle Dame sans Merci

Hath thee in thrall!”

I saw their starved lips in the gloam,

With horrid warning gaped wide,

And I awoke and found me here,

On the cold hill’s side.

And this is why I sojourn here,

Alone and palely loitering,

Though the sedge is wither’d from the lake,

And no birds sing.

There are many interesting and valuable discussions of Keats’ poem and these can be found on many academic websites. For our purpose here, I would like to go directly to Waterhouse’s dark painting, one which draws us into the dangerous world of the Dame:

John William Waterhouse, La Belle Dame Sans Merci , (1893) . Hessiches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt

Here we see the knight falling prey to the Dame, and Waterhouse has ‘illustrated this danger with great imagination: the woman winds her long luxuriant hair round the knights neck and so pulls him towards her. She may appear innocent, but with several skeins of hair, she is weaving a noose for her victim. The chilling impression this projects is underscored by the dark undergrowth in which the pair seem to lie imprisoned’.

Note that there is no mention of the long tresses in Keats’ poem …this is a Waterhouse addition (or a ‘translation’), one that is in keeping with a popular image in the second half of the 19th century of a man strangling in a woman’s long hair, the weapon of the femme fatale. It is also interesting to note that, in Victorian terms, loosened hair signified loose behaviour (respectable Victorian ladies wore their hair bound tightly).2

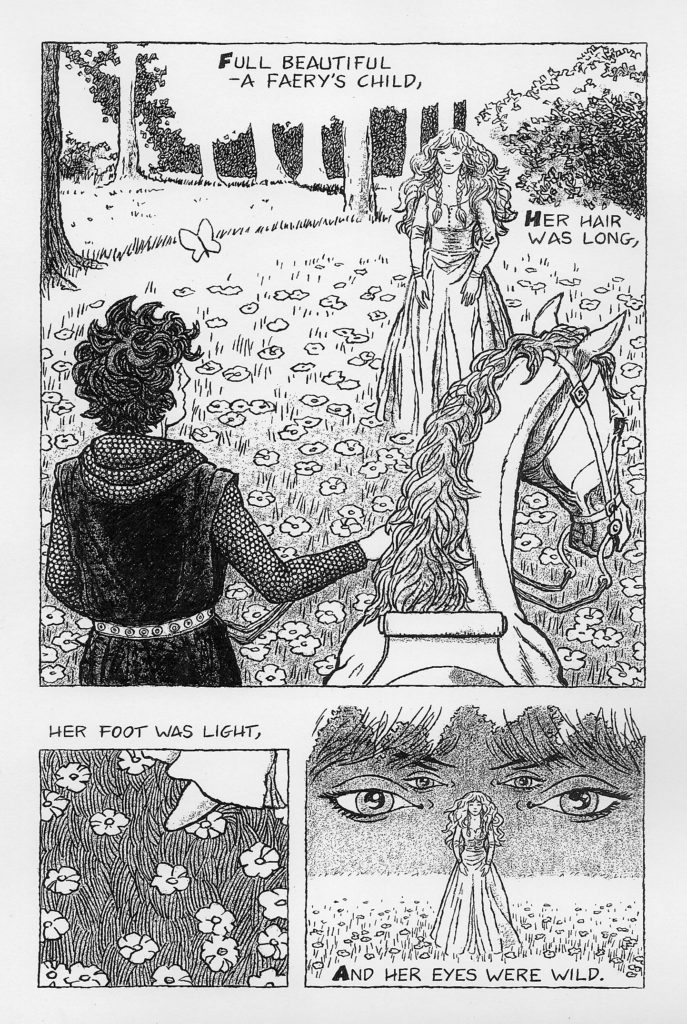

La Belle Dame Sans Merci has been a popular figure into this century and Keats’ poem has, of course, generated much artwork beyond that of the pre-Raphaelites. You might enjoy a contemporary graphic novel version of the poem by Julien Peters. Some of these drawings were exhibited at the Keats-Shelley House in Rome, 2012.

I am particularly intrigued with the way in which Peters re-creates the wildness of La Belle’s eyes, a wildness and threat that is concealed behind her apparent innocence.

The assumptions about the Victorian woman, in all of her forms, generated a host of powerful artworks, most of which were based on poetic texts that preceded them, reaching as far back as Homer to the more contemporary early-19th century poets. Similarly, Tennyson’s ‘Lady of Shalott’ was written early in the 19th century (1830), and had a profound influence on the later artists of pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In the next section, The Lady and Her Illustrators’, we will see how the varying ideas of womanhood affected the translation of Tennyson’s poem into works of visual art.

NOTES:

- Henk van Os, Femmes Fatales, 1860-1910, Groninger Museum, (Catalogue for exhibition), p. 8

- Ibid, p. 148

Don’t forget the women pioneers of the old west, the Annie Oakleys of this period. There where some very brave women of strength and fortitude who walked the Oregon, Mormon and California trails( 15 miles a day for 6 months). Many were widowed along the way and still braved the wilderness and settled in the untamed western territories.