THE POETRY OF JOSEPH STANTON

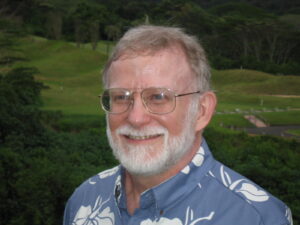

Joseph Stanton is a Professor Emeritus of Art History and American Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Four of his seven books of poems are ekphrastic: Imaginary Museum: Poems on Art (1999), Things Seen (2016), Moving Pictures (2019), and Prevailing Winds (forthcoming in 2021). His other three collections are A Field Guide to the Wildlife (2006), Cardinal Points (2002), and What the Kite Thinks: A Linked Poem (1994). The last named book is a collaboration with renshi poet Makoto Ōoka and two other writers. His poems have appeared in such journals as Poetry, New Letters, Harvard Review, Antioch Review, Ekphrasis, Ekphrastic Review, and New York Quarterly. He occasionally teaches ekphrastic poetry workshops, such as the “Starting with Art” workshops he has taught at Poets House (in New York City) and at the Honolulu Museum of Art. His other sorts of books include Looking for Edward Gorey and The Important Books: Children’s Picture Books as Art and Literature. As an art historian, he has published articles on Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Edward Gorey, Maurice Sendak, and many other artists. He has frequently collaborated with visual artists, playwrights, composers, and other poets.

(jstanton@hawaii.edu)

Contents:

Introduction

An Interview with Joseph Stanton

Selected Poems from Imaginary Museum: Poems on Art, Things Seen,

Moving Pictures, and Prevailing Winds.

INTRODUCTION

I was first introduced to Joseph Stanton’s poetry in 1999 during a Word and Image conference at Lund University in Sweden, where he participated as the conference’s poet-in-residence. During Stanton’s reading from Imaginary Museum (1999), I was struck by a unique (and sometimes startling) view into paintings that had long been so familiar to me. Over the intervening years, Stanton’s publications of ekphrastic poetry have been critically acclaimed, and he has been rightly praised as “both a scholar and masterful practitioner of ekphrastic poetry” with an “exquisite sense of perception and insight as he indulges readers with new ways of seeing art” (critique of Moving Pictures), as a poet of the “richly visual”, a writer who is “so sensible to aesthetic signs, so gifted for reading the canvases into poetic language” (Hans Lund). His are “poems of mood and meditation, and they make you want to look at the paintings again and at these wonderful poems again and again” (Tony Quagliano), poems that turn on a “masterful translation of image after image into the essence of its own perceived light” (Laverne and Carol Frith).

Stanton’s ekphrastic poetry carefully guides the reader through a wide variety of paintings, often on unexpected paths that enlarge our understanding of painting and painter, and opens our eyes to the myriad possibilities that a keen poetic imagination can bring to a visual work of art. In the following interview with Joseph Stanton, I had the opportunity to explore some of the ideas that lies behind his creation of ekphrastic poetry.

AN INTERVIEW WITH JOSEPH STANTON

Question: Your background and expertise in both art history and literature provide a perfect springboard into paintings, unlike the backgrounds of most writers and critics (and I include myself here) who are essentially “moonlighting” in the field of art history. Could you comment on the ways in which the combination of these two academic fields have contributed to your work?

Stanton: I began life as an entirely literary person with a literary BA and a literary MA. I was extensively trained as a literary historian, but, after I received my MA in English and American Literature, I decided, at first, not to pursue a PhD because it seemed there were so few jobs available in the humanities. In the early 1970s, in my pause from full-time graduate studies, I worked at writing textbooks and drama reviews. During that time I was simultaneously starting to write lots of poetry and beginning to become an art historian. In whatever spare time I had, I hung out in the Honolulu art museum. Also, I began to take art history courses and to read at length in art history. The bulk of my art historical training happened during my PhD work in New York City, where, starting in the mid 1970s I studied in the summers and in various year-long leaves from my writing jobs. I am an odd creature in that I started out over-trained as a literary historian and then switched to being over-trained as an art historian. The ekphrastic tendency dates back to interests I developed even while I was still primarily a literary historian. I cannot judge what is the right way for others to approach ekphrasis, but, for me, my ekphrastic bent was the result of three passions. I have been (and remain) a dedicated practitioner of literary history, art history, and poetry writing. As an interdisciplinary scholar, I have, of course, been selective in my focus. I intensely study what is necessary for my several fields. It just happens that my fields involve some topics that are entirely literary, other topics that are entirely artistic, and still other topics that involve the intersection of the literary and the artistic. As I have discussed elsewhere, I was influenced by such ekphrastic poets as W.H. Auden, William Carlos Williams, W.D. Snodgrass, and Richard Howard. My obsession with art-inspired poetry led to my collecting examples of ekphrasis. I continue to collect examples of responses to art by other poets. I have bulging files of examples, and I have on my shelves many books and journals in which such examples can be found. The practices of other poets are of great interest to me. Furthermore, I have developed a lifelong interest in prospects for collaboration with other artists–whether literary, visual, or musical.

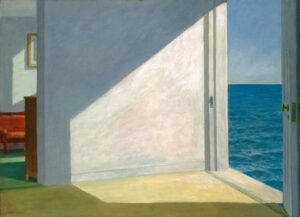

Question: I’m particularly intrigued by the important place that Edward Hopper has in all three volumes. I wonder if you might explore your interest in Hopper’s work as well as your interest in him as an ‘artist at work’ and the process of making.

Stanton: I could write many pages in answer to that question. For all the ways Hopper’s works seem to tell us about the world at large and America in particular, it is well to keep in mind how frequently Hopper declared in his various remarks that his works were self-expressive captures of his own inner self, that what he wanted was “to do myself.” Asked to explain why he gravitated to certain subjects, he explained, “I do not exactly know, unless it is that I believe them to be the best mediums for a synthesis of my inner experience.” Though Hopper’s works reflect his inner experience, they remain mysterious and do not resolve easily into simplistic stories. Hopper images are, I think, provocative to ekphrastic poets because they present scenes frozen in place that seem to have multivarious narrative implications and meanings, while at the same time being beautiful works of art. We need to remember that Hopper loved stage plays and movies. Forms of theatrical and cinematic drama influenced him in many large and small ways. It is interesting, too, that many dramatists and filmmakers have, in turn, been influenced by Hopper. My fullest statement on the subject of narrative implications in the works of Hopper can be found in an article I contributed to the journal Soundings in 1994. That article, “On Edge: Edward Hopper’s Narrative Stillness,” can be accessed online through JSTOR.

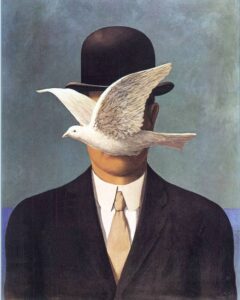

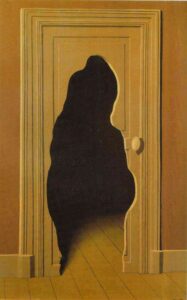

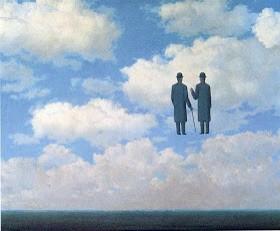

Question: Aside from Hopper, you give particular attention to René Magritte in your poetry, an artist whose work seems to lie on the opposite side of the spectrum (realism versus surrealism). Could you comment on your interest in Magritte’s approach to the “trappings” of our daily lives?

Stanton: My interest in Magritte is related to my interest in Hopper. In a sense, they seem opposite sides of the same coin. Hopper finds mysteries in the real, while Magritte finds realities in the mysterious. Both artists are endlessly suggestive of possibilities for poetic response. It is quite possible that I may write more poems in response to the works of Magritte in the future. I continue to study and re-study Magritte. I find his work deeply moving. He dreams within or just beyond the “trappings of our daily lives.” I find that in some of my ekphrastic poems I am, in a sense, performing the visual work as if it were a dream. The very different sorts of mysteries we encounter in Hopper and Magritte lend themselves to performances of that sort. Often my poem takes the point of view that the world I am presenting is the world the artist created—I realize, however, that I cannot make truth claims for my performances. As I write my poems, I am trying with the best of my ability to tell the truth about the world of the work of art, but I cannot make claims about the success of my attempt to “get it right.” I prepare for the writing of each poem by engaging in many weeks, days, and hours of research on the artist, the artist’s work in general, and the specific work I am trying to write about. There are, however, no guarantees. If I feel the poem does not achieve a truth or is not a success as a poem, then I have to abandon it and hope I will be able to rescue it at some future time. Although I do gravitate to certain preferred artists, such as Hopper and Magritte, I have written poems inspired by artworks belonging to many historical periods and cultural traditions.

Question: Not only have you made a vast contribution to our available body of ekphrastic poetry, but you have shared your knowledge of writing in workshops titled “Starting With Art”. Could you give a brief description of your courses.

Stanton: My “Starting with Art” workshops focus on finding inspiration for poetry writing in many sorts of works of art. Although the emphasis is often on writing in response to paintings, I also have exercises that encourage writing in response to music, architecture, dance, theater, movies, literary works, gardens, and so forth. One of my primary points is that any sort of thing or thought can inspire a poem. I provide many examples of ekphrastic poems (again the emphasis is on poems inspired by visual works, but I also offer examples of poems inspired by the other arts.) Among my many handouts is a substantial document I call “A Practioner’s Poetics for the Art-Inspired Poem.” One of the sections of that document provides a list of strategies that can be employed as one endeavors to write in response to a work of art. Other handouts are activity-focused documents in which a writing exercise is described and various examples of that sort of writing are examined. Preparations for teaching my “Starting with Art” workshops can be very time consuming for me because I prepare “powerpoint” materials to project on the screen in the classroom to support my commentaries and to stimulate discussion. My workshops are all about encouragement. I am not a harsh teacher in that context. I find aspects of each student’s work that I regard as encouraging. I set a tone in the classroom where constructive remarks are expected from everyone. I expect group members to help one another rather than to compete.

Question: Could you discuss the complexities of poetic choice that inform your approach to a particular painting or painter?

Stanton: As a writer, I respond to works of visual art in a very wide variety of ways. Many years ago (I think it was in the 1980s) I developed a list of strategies that the ekphrastic poet might use to approach the task of responding to a work of art. I based that list on both my own practice and on my examination of the great many examples of art-inspired poetry that I had gathered. In 2012, I made a public presentation in which I discussed eight strategies that might be employed by an ekphrastic poet. The topic of the conference was announced as “WordImage/ImageWord.” It was hosted by New York City’s School of Visual Arts. I provided examples for each of my strategies (usually one poem by me and one poem by someone else). Here’s the list of strategies I offered at that time:

1. Describe the work of art

2. Interpret it

3. Render it as a Keatsian “frozen moment”

4. Write a monologue or dialogue

5. Write a third-person narrative to tell the story observable in the artwork

6. Write a mini-biography of the artist or a personage presented in the artwork

7. Comment on the situation of the artwork as a thing in its context (picture-on-a-wall, statue-in-a-place, object, artifact, etc.)

8. Write a surrealistic (dream-like) piece (in other words, perform the artwork as if it were the poet’s dream)

In offering this list to students in my “Starting with Art” workshops, I also comment on the inadequacy of the list and encourage participants to brainstorm their first-draft notes with whatever comes immediately into their minds as they consider the artwork. Although I encourage my students to adopt a spontaneous approach, my own personal working method involves a preliminary step that is not practical to insist upon in a workshop context. As I prepare to write in response to an artwork, I engage in an extensive research phase. I read everything that I can find on the artist and artwork. In many cases, I read or re-read dozens of books and articles as I prepare to write an ekphrastic poem. It is important to note, however, that my art-inspired poems are not burdened with that knowledge. My research is grist for the mill, but, when I start brainstorming the poem, I put the research off to the side and endeavor to perform the artwork as a poem. My poems are not essays. They are always poetic “performances” in response to the artwork. The job of an ekphrastic poet is to write a good poem. I might hope my poem will be “right” about the artwork, but the responsibility of a poet is always to write a poem that succeeds as a poem. (Or, at least, tries to succeed as a poem.) I have occasionally mentioned in my workshops that there are at least two other strategies they might want to keep in mind:

9. The poem can be a parody of the artwork (or can be in some other way comic)

10. The poem can be controlled by its form (a form can impose a shape on the piece and can also suggest the content of the piece)

Again, although I have, over the years, thought a great deal about the strategies that an ekphrastic poet might adopt, I do not think about those strategies when I sit down to write an art-inspired poem. My focus is all on the artwork and on my responsibility to endeavor to write a poem that will, hopefully, have value as a poem and as a response to the artwork under consideration. Key to that endeavor is the importance of revision. I need to keep writing until the poem becomes the poem it needs to be.

Question: I would like to ask you the question that continues to be a point of argument among scholars: Is art historical writing “ekphrasis”?

Stanton: The traditions of art history and ekphrasis can be regarded as interwoven. Giorgio Vasari is often seen as important to both traditions. Certainly the best art historians include in their writings passages and sometimes entire essays that could be discussed in relation to ekphrasis. It could be argued that art historians are at their best when they strive to adequately describe a work of art that they admire. The same could be said of art critics. It should be pointed out, however, that art historians have many things to do besides describing artworks. An historian of any sort has responsibilities for telling stories about what happened when and why with regard to historical circumstances. They need to tell us about changes in the practice of the arts and about how art training and patronage developed. There is much that is prosaic that historians must chronicle. While it is not necessary to talk about art history as a form of ekphrasis, it is valuable to remember that art history informs and inspires ekphrasis. One cannot forget, also, that there are many stunning examples of ekphrasis available in the works of art historians and art critics. Walter Pater, for instance, was renowned for his passages on Leonardo, Giorgione, and others. John Ruskin, too, was much celebrated for his influential historical and critical pieces. Certain essayists are associated with the eloquent advancement of the reputations of particular artists. Roger Fry on Paul Cézanne is an example of that.

Question: You have mentioned that you often collaborate with visual artists. Could you provide some background on an artist/writer collaboration?

Stanton: Among my best and most productive collaborations with artists are my several collaborations with Adam LeBlanc. In 2020, I collaborated with LeBlanc on “Nights on B Street.” That exhibition was based on a work LeBlanc created—in its original, non-collaborative, version—in 1993. The seven detailed urban scenes were inspired by LeBlanc’s experiences and observations in various cities. He had in mind primarily New York City and Boston, the Eastern cities where he had spent the most time. “Nights on B Street” was exhibited at the Honolulu Academy of Art and was widely praised. I admired the show and often talked about it with LeBlanc. From time to time over the years, LeBlanc and I chatted about “Nights on B Street.” I mentioned more than once that I would like to have the opportunity to write poems in response to the “B Street” pieces. When Gallery ‘Iolani greenlighted the show, I began work on my “Nights on B Street” sequence. As with our previous collaborations, LeBlanc and I talked and talked about the works—sometimes in person, sometimes over the phone. I had chances to see the works, and I also had photos of them so that I could consider and reconsider what was happening or about to happen in the urban scenes. For me, the world of “Nights on B Street” was all about New York City. I first spent time in New York City in 1979-1980. I was there to work on graduate studies. Those studies brought me back again and again to New York City throughout the 1980s. After receiving my PhD in 1989, I continued my annual visits to New York City. Thus, although LeBlanc’s memories prompted directions in my “Nights on B Street” sequence of poems, my personal experiences of the Big City fed directly into my “B Street” musings. It is interesting that, despite my heavy reliance on my own memories, LeBlanc found in my eleven “B Street” poems much that resonates with his own urban recollections. Large-print copies of my eleven poems were displayed in the Gallery next to the appropriate pieces. LeBlanc and I regard the 2020 “Nights on B Street” exhibition as deeply collaborative—with poems that evoke the art pieces and art pieces that give visual form to the poems. Although the pandemic limited the number of people who could witness “Nights on B Street” in person, the Gallery was able to make a brief YouTube video about the show. Here’s the link to that video:

Question: What about your collaborations with other poets?

Stanton: My most interesting collaboration of that sort resulted in a book-length linked poem, What the Kite Thinks. The leader of that collaboration was the Japanese poet Makoto Ōoka, who engaged in similar modernist, linked-poetry collaborations in several parts of the world. Ōoka’s idea was to continue the tradition of Japanese linked verse, but with rules that enabled a free-verse approach. Ōoka invented the term “renshi” as the name for this new form of collaboration. Each poet in our collaboration was asked to write each link by taking the last line of the previous poet’s poem as the title for his or her new poem. As the long poem developed and unfolded, all the participants in the renshi were asked to be responsible for the quality and nuance of the entire sequence. It was an exciting project in which every turn was a surprise, while every turn contributed to the unity of the sequence. The other two participants in the renshi were Wing Tek Lum and Jean Toyama.

II. SELECTED POEMS

I. Selections from Imaginary Museum: Poems on Art (Time Being Books, 1999)

Giorgione’s The Tempest

The Man:

The storm was what it was and nothing more,

a cool disturbance of September air,

lifting branches and their leaves—

still green, all green, in rush of wind

that means the world is changing and we could

be part of what is new.

After the clouds cleared we walked out

under the stars and the half-full moon,

and the world was moist and clean,

and we were striding beyond ourselves,

our arms around each other down the streets

of sleeping Castelfranco,

as if we were, or could be, a new world.

Sometimes, when I remember her I see me,

off to the side, admiring.

But always she is gazing straight out

of the dream, straight out at the long-gone me,

seated uncomfortably,

front-row center of memory theatre.

Unforgettable brown eyes meet mine

to say, “Yes, I am still here.

Yes, you are still there.” In her eyes still

is the light that passed between us and is

still passing between us.

It is the light I work by, the light

that makes every woman her. Why do I

remember her always

in the broken countryside of home,

suckling a child whose tiny face seems

its mother’s tiny echo?

Could that mother or her echo know

that I am already renowned in Venice

and in Rome, and dying?

The Woman

In the electric air of the approaching

storm we became each other, hiding

under shelter of the bridge.

We were what we were and nothing more.

He lifted me and kissed me and loved me,

and I loved him back, I thought,

but I will remember him always

with his back to our town, standing, one arm

akimbo, the other holding

his staff, his eyes filling with distance.

He would learn to paint, he always told me,

when I asked what was to come,

and then on the eve of his leaving

the storm brought us together and brought me

this child that seems an image

of his father, his father who has gone.

When I think back it is always to that storm,

that sudden autumnal storm,

the electric charge passing between us

again and again. Does a child always come

when there is so much love

two people cannot contain it

and a third must be made?

The Scene

Behind them the late-afternoon sky

is broken by a storm whose lightning

jags above the towers

of the white stone town of Castelfranco.

Reflected in the greenish-blue shimmer

of the stream are the bridge,

the castellated walls, the grassy banks,

and the thick foliage of ilexes

and flowering acacias.

These trees shake in a sudden breeze, leaves

glistening in the momentary light.

The figures seem caught by chance

in the pulsing light of the lightning flash.

Against the swollen, aquamarine clouds

and above the pale towers

that bright, dangerous scribble of white fire

will remain in the space between them.

Pieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death

There is no escape.

At sea ships split and crumble like rotted eggs.

Above me on the hilltop wheels of no chance

turn in the wind’s agony,

taking crucifixion for a spin.

The turrets of our harbor fortress

are already tightly packed with our impossible enemy,

the unstoppable battalions of bones.

It is as if they had always been here,

as if we were not, a few minutes past,

enjoying a casual meal of crusty bread,

dark savory porridge, and tart red wine

on the edge of town, near the ruined cathedral,

with Hans and his new friends,

elegant all in the slickest of silks,

when all this erupted from the ground.

Now these instant apocalyptic gardeners

are clattering determinedly from door to door.

They reap us routinely,

like so much overripe grain.

They, they! But they are us:

reversed, turned inside out,

and reduced to the core;

rough drafts for a rebirth

we can have no confidence in;

grim satires on our fragile desires,

who put on our clothes,

clutch our gold,

spill our stone-cold wine.

Hans, ever the pale poet,

sings what must be his last love song

to a woman who still

wants to be his inspiration.

Behind him, with skull-wide grin,

his death accompanies on mandolin.

Across the field our King lies sprawled

in a fatal stupor of disbelief,

attended by a skeleton staff.

To the north the horizon blazes,

a backdrop for a smoke-blackened,

knockerless bell

slung from a blasted tree

by a thin, grim kneller,

our final silhouette of silence.

There must be a design to all this.

I lean against it with the frail heft of my body,

clutching the hilt of my sword.

Pieter Bruegel’s The Harvesters: August

The eye must enter this blaze of grain

that comes forward out of the frame,

a blond forest of ripened light.

The fastened sheaves march motionless

on their legs of broken gold.

They are becoming the reason

for this day’s work,

its stack and haul,

in the ocher glaze

of a centuries-old afternoon

the wind rises through

fresh each time we look.

In the distance hills slipcase into hazed air,

where always there will be an ocean waiting

at horizon’s edge

paced by tiny pale silhouettes of ships

that come and go in delicate silence.

A heedless sleeper with emphatic sprawl

makes himself the hub

of this wheel of harvest and hungering,

the closed eye of this fecund calm.

His paused desires are the tight nutmeat

in the shell

of this moment,

secure in the clutch

of all that cannot resist

the spiral in

to sleep.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Paolo and Francesca

An open book across them lies, lap to lap,

but they lean together, read no more.

The moment’s rising in them root to sap,

their lives closing behind this open door,

while Dante and friend, who walk the dark between,

tourists in a Hell one of them has dreamed,

regard the damned and not their loving scene:

such loves are final and cannot be redeemed.

The winds of darkness twirl the lovers round—

an embrace that knows no ending, no relief.

What both Dantes feel for them’s profound,

an envious pity, a joyous grief.

Their Night’s a spin through love’s fierce weather,

doing without death’s marble calm forever.

Georges Seurat’s Evening at Honfleur

Seurat’s science calls horizontals calm,

but down the slope of pilings they turn sad,

while sunset breaks white against the solemn

black of jagged rock. His light’s a stern, mad

landscape divided into tiny balls.

This picture’s machine calculates why

one pale dot hued against the next recalls

a cool gaiety not unlike the sky

spread out above a certain slant of shore.

Somehow we understand this riddled air

and suspend it in thought above Honfleur

because Seurat saw something like it there.

His art’s divisioned dots define a scheme,

conceived as theory, that we must see as dream.

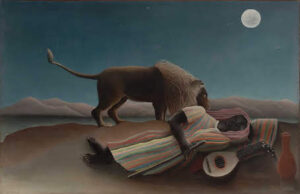

Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy

Henri has wrapped his gypsy

in a dream of many colors,

stripes of pleated gauze, gleaming.

Above and beyond he makes

the silence a place, dark blue

but punctured by light.

A white-faced mask floats,

smiling, over a beige and ocher

undulation of desert.

At the center of this silence,

where sky and sand devise a horizon,

a browned brooding of violence

appears: a shadow carnivore

breathing the edge of sleep,

a ceramic emblem of devouring

who will soundlessly pass on,

leaving the toy-doll gypsy,

her tightly tuned tan mandolin

and orange jar of night-cooled air

to whatever music the stars

can, unwittingly, prepare.

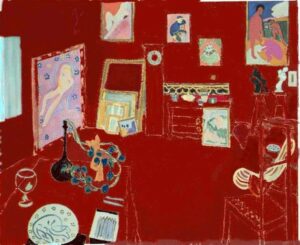

Matisse Replies to Snodgrass: A Poem About a Poem About a Painting

His mind turned in in concentrated fury, /

Till he sank. . . / His own room drank him.

—W. D. Snodgrass, “Matisse: ‘The Red Studio’”

Looking into my red studio,

were you surprised to find no one there?

Calm yourself, my friend. I was only out

of sight, preparing the space for visitors.

Since I am not part of what I see,

I leave myself unframed. Do you understand?

This room is decorated for pleasure,

colored warm to comfort your needled heart.

My art is an embrace, not a devour.

Come inside. A painted chair awaits you.

I will be there. Together we will share

a refreshing drink of my bright scarlet air.

Magritte Variations

The man in the bowler hat is looking

this way and looking that. Everywhere

he looks there is the same, not unpleasant,

desolation. A crescent moon floats over

each turn of thought, as if consolation

were not impossible. But the empty place

is so great it sometimes fills him with nothing

in particular—a bird cage, some floating

words on white, a doorway, a candelabra,

a vast ache echoing as laughter.

Sometimes he walks down to the cobblestone

bridge and pretends he does not remember

who leapt into the quiet river

while her family slept. He sleeps always

now when he paints, dreaming of her.

Sometimes she stands by the bridge, posed

in lovely, formal white—a blue flower

where her face should be. Sometimes her face

has turned into the sky’s blue or into stone.

Sometimes the sky is red as wine or blood

above the rooftops, and a gigantic

white rose grows up from the cobblestones.

Sometimes he is a man riding a racehorse

faster and faster through the night, head down

for speed, whip in hand, trying so hard,

so very very hard to get there. Sometimes

it is she who is riding, off in the distance,

glimpsed between trees. Sometimes the harness bell

appears as monolith or stage prop, often

accompanied by its friends, the chess pieces.

At such moments sorrow seems to have sailed

out to sea, and the fruits to be gathered

on shore seem souvenirs of eternity.

Sometimes the fruit floats above the sea

sporting tables reserved for dining,

or we see, above the iron waters,

rocky islands topped by Spanish castles.

If we didn’t know better, we might think

all this dangerous—especially the way

everything keeps turning into everything else—

bottle becoming carrot, fireplace

becoming train depot, and almost everything

becoming stone. The man in the bowler hat

wants to get away from it all but finds

that everything, at the last, turns back

into mind. The more he turns his back

upon himself, the more he returns, falling

like rain, a thousand men in bowler hats falling

and falling through a blue sky with white clouds

that is also a picture on an easel

that is also a window and a chess piece

and an eye full of sky—an inner eye

that sees a woman who jumped into a river

while her family slept, her face, when they

brought her up, covered by her night clothes.

This dream, too, is not a pipe.

Edward Hopper’s New York Movie

We can have our pick of seats.

Though the movie’s already moving,

the theater’s almost an empty shell.

All we can see on our side

of the room is one man and one woman—

as neat, respectable, and distinct

as the empty chairs that come

between them. But distinctions do not surprise,

fresh as we are from sullen street and subway,

where lonelinesses crowded

about us like unquiet memories

that may have loved us once or known our love.

Here we are an accidental

fellowship, sheltering from the city’s

obscure bereavements to face a screened,

imaginary living,

as if it were a destination

we were moving toward. Leaning to our right

and suspended before us

is a bored, smartly uniformed usherette.

Staring beyond her lighted corner, she finds

reverie that moves through

and beyond the shine of the silver screening.

But we can see what she will never see—

that she’s the star the star of Hopper’s scene.

For the artist she’s a play of light,

and a play of light is all about her.

Whether the future she is

dreaming is the future she will have

we have no way of knowing. Whatever

it will prove to be

it has already been. The usherette

Hopper saw might now be seventy,

hunched before a Hitachi

in an old home or a home for the old.

She might be dreaming now a New York movie,

Fred Astaire dancing and kissing

Ginger Rogers, who high kicks across New York

City skylines, raising possibilities

that time has served to lower.

We are watching the usherette and the subtle

shadows her boredom makes across her not-quite-

impassive face beneath

the three red-shaded lamps and beside

the stairs that lead, somehow, to dark streets

that go on and on and on.

But we are no safer here than she.

Despite the semblance of luxury—

gilt edges, red plush,

and patterned carpet—this is no palace,

and we do not reign here, except in dreams.

This picture tells us much

about various textures of lighted air,

but at the center Hopper has placed

a slab of darkness and an empty chair.

Edward Hopper’s Gas

It is late. This chance may be our last.

Although we know we need much more than gas,

this opportunity must not slip past.

The narrow road ahead will not go fast;

it curves into a dark-forested mass

of trees. This chance may be our last.

The day is done, the last, long shadows cast.

Summer’s gone, and autumn’s seared the grass.

We know this seasoned hour will not last

and should not go unnoticed, overcast

by thoughts of things that never came to pass,

opportunities that slipped by in the past.

The Mobil pumps must be secured, locked fast.

The owner wonders if we will bypass

him here. He knows this chance may be our last.

His station will stay lighted till we’ve passed.

When he shuts down, the darkness will be vast.

It is late. This chance might be our last,

an opportunity we might decide to pass.

Edward Hopper’s Rooms by the Sea

A house that opens wide its door

to an open expanse of sea is more

than a machine for living, and less.

This opening to an abstract wedge of blue

makes the infinite an idea of horizon

that casts on floor and wall a sad, finite

hexagram of pale oceanic light—

a heightened palette’s subtle alchemy,

white become gold, that we must see to glow—

a trick, but also a joke—

a piece the painter knew would be called

abstract and surreal and real, too.

Still,

a scene must be a life—

trick, joke, and all—and we can see

that someone has lived here,

around the frame’s corner

and into the adjoining room,

where the faded rose of the sofa rises

to dispute the brown smudge of the bureau.

Everything they say they have said before.

Even the worn green rug knows their songs

by heart and will not listen

as the threadbare, angry voices rise and fall.

Meanwhile, the waves outside the dreaming doorway

have their own voices. “Mine, mine, mine,” they cry

as they break against each other.

II. Selections from Moving Pictures (Shanti Arts, 2019) Used with permission of Shanti Arts LLC and Joseph Stanton. All Rights Reserved

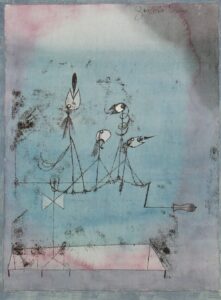

Paul Klee’s Twittering Machine

A machine made of birds

composes a music,

each bird

a figure on the scale,

a note of the song,

twittering

with open beak

and exclamation point tongue

played by the turning

of the machine’s crank.

It’s as if a sweetly cruel device

compelled

the tree of the world

to love the sky

or, at least,

to sing its tune.

René Magritte’s The Unexpected Answer

The way out or the way in

might be a jagged hole

that breaks through

where you need to go,

despite the door

you might simply have opened.

Your advance cracks

a passage unexpected into

a darkness grim and oddly inviting.

The floorboards carry you forward

as if yours were an ordinary life,

while the absence of light

in the place that waits

would seem to be horrific

and comic all at once,

like the life-and-death

exits of Bugs Bunny

and Road Runner that rely

on impossibilities

through which no nemesis

could pass.

René Magritte’s Infinite Recognition

A walk with a friend into the endless sky can be instructive,

especially when it’s undertaken a few years before one’s death,

especially when the friend is just another version of oneself.

Magritte enjoyed profoundly the pointlessness that is the point of everything,

but it is hard to believe that absurdity

is all the horizon has to offer.

He needed to explain the silliness

of it all to himself over and over again,

as he does here in full—

Magritte brandishing his finger of index

to explain to Magritte

what they both understood to be

incomprehensible

but not all that

complex.

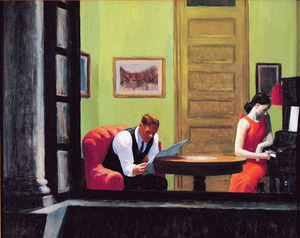

Edward Hopper’s Room in New York

Seated in the room’s one comfortable chair

a husband hunches forward, intent upon his paper

as if his life depended on the scores he finds there.

Just home from work

he has not yet loosened his tie,

nor spoken with his wife

who is wearing her bright red dress,

the one with the bow in back that

comes easily undone.

She knows he has not noticed

so she plunks the keys of her piano

to say to him softly

that she is there

and has been waiting all day

for him.

The room glows—

yellow walls, oak table and door,

the rosy tones of the man’s chair and the woman’s dress.

Something could come of this.

III. Selections from Prevailing Winds (Shanti Arts, 2022 forthcoming)

Isamu Noguchi’s Brilliance

Noguchi spoke basalt best of all.

It was his most intimate tongue,

harboring, as it did,

the double-ness

he so much loved.

In basalt he found a stone

that could be

dull skinned,

as red and rough

as the earth itself,

but with an interior

he could polish

to a gleam

of volcanic ink,

darkest of mirrors.

Basalt he knew as the core

of all erupted worlds—

even ocean floors,

even the moon and mars

hold basalt to heart.

In 1982 Noguchi

stacked three,

mismatched

chunks of basalt

as a column six-feet tall.

With diamond-edged saw

and diamond-tipped drill

he ripped

and broke

the igneous rock.

In some spots he polished

the inner revelation

to a blue-black sheen,

alternating rusted shell

and lava-liquid soul.

Then he wielded bamboo,

the most antique of tools

to pock a line

of marks

in ruddy skin.

When it was finished,

he called it Brilliance,

though he knew

it was less than that

and more.

Isamu Noguchi’s Red

A tall rectitude of red travertine,

one of Noguchi’s monumental zeros,

full of nothing and nothing if not full,

speaks to his Euro mentor, Brancusi,

yet, also, seems as Zen as Zen could be,

wabi as well as sabi,

a statue that resides in a West that is also East,

Honolulu to be exact,

where Japan and America

cross in more ways than one,

a sculpture offering two sides,

an ancient rune whose tune

also declares the modern,

and we can see, too, that the smooth

is backed by the rough hewn,

balances struck and striking,

primitive, yet sophisticate,

powerful, yet simplistic,

rock that is also flesh,

containing crystals that spark light,

a sun setting on a Pacific expanse—

touching upon his mother and his father

as he often did in mind,

seeking, again,

the balance that is the everything

and the nothing at all.

Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for a Self Portrait

A mirror, he feared,

could be full of tricks

so why not save face

by tripling it?

Bacon knew existence

questionable

so he never stopped questioning

what he himself

might be.

He loved to see in threes

with his triptychs

speaking to a holiness

of altered pieces.

Suggestive swerves

fleshed against absolute dark,

constituting a reliquary:

an elusive self—

his own, for instance—

bespeaking a broken

remnant

of martyrdom.

IV. Selections from Things Seen(2016). Used with permission of Brick Road Poetry Press and Joseph Stanton. All Rights Reserved

Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning

Nothing stirs on Seventh Avenue but light

and color, red so red and green so green,

notes that complement the bright

harmony the mind strives to see,

a long-shadowed Manhattan morning,

a subtly melodious 1930

of windows and doors that sing

a broad expanse of street,

but no one seems to be at home here

except the woman painted out in window four,

whose ghosted life returns now as pentimento,

as she suddenly throws open her window,

and cries,

“Oh, come in, come in my dear.

It’s been so long, and we have missed you so!”

Edward Hopper’s Night Windows

The picture is all about

what the surrounding absence

makes of light

inside where the woman dwells

with her window open for air,

undressed

to her final grace note,

her pink slip.

Naked almost

she knows herself to be

but thinks she has held herself

inside a private moment in 1928,

primping

for what she hopes

her night will bring.

Held tight to her only life,

she’s not in the least aware

of what Edward Hopper

manages to see,

riding the evening El,

accompanied by

those crude voyeurs,

you and me.

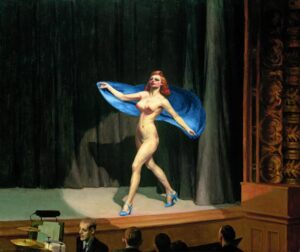

Edward Hopper’s Girlie Show

Puritan by birth, sensualist at heart—

Hopper was struck by something

he wanted to say on Valentine’s Day, 1941,

while gazing at a buxom woman,

disrobed and prancing,

on the last stage of the Minsky family’s

grand wheel of burlesques

in the old Republic on 42nd Street.

Fed up with Fiorello

and The Little Flower’s tedious complaint

against displays of flesh

and wanting to say so in paint,

Eddie asked Jo to pose for him

again and again—

their studio on the top floor

of No. 3 Washington Square North

become a theater runway,

another round in the game they played—

Jo posing, actress that she was,

for another of Eddie’s many women.

The first sketch of her in conté crayon

very tenderly rendered

her fifty-year-old body,

nude and lovely,

her arms raised in the stance

of the dancing Girlie,

her legs turned toward the artist,

squinting at him as if to say,

“Is this enough, Eddie,

Can I stop now PLEASE,”

shivering but holding her pose,

her firm breast upturned to a degree,

her loveliness especially lovely for him,

as he keeps her in this difficult pose

for his own joy,

and hers, too, if truth be told,

in the intimate Times Square

of their intensely complicated

intersection.

***********************************

WITH THANKS TO JOSEPH STANTON FOR HIS THOUGHTFUL ANSWERS TO MY MANY QUESTIONS AND FOR SO GENEROUSLY CONTRIBUTING HIS POETRY TO THIS WEBSITE.