INTRODUCTION

In Part I, we considered the different ways in which poets represent the visual arts in their own medium: the word. Part 2 focuses on Illustration and, in turn, the ways in which the visual arts represent texts in their own medium: the image. Recalling Lessing’s dictum that the arts do not represent in the same way, what do we make of illustrated texts?

Do you recall your earliest picture books, those wonderful journeys into stories filled with illustrations, where words and images combined to create a rich and magic experience? Indeed, in these books, the images are as important as (or even more important than) the words, as they are used to fill out or explain the narrative itself. Of course, illustration is not limited to books and it frequently takes the form of independent works of art that are based on familiar narratives (the Bible, historical events, mythology, and other literary sources). Recalling the different paintings based on ‘Judith and Holerfenes” ( discussed in Part I, Chapter 2 ), you will remember that illustration really is just another kind of ‘translation’ and, like translation, it is largely subject to personal and/or cultural factors. And, of course, as we know by now, this kind of translation between the arts -and its subjectivity – is what ‘ekphrasis’ is all about.

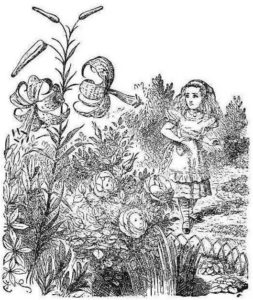

So how does this work with translating a text into a visual work of art? To ‘illustrate’, so to speak, let’s have a look at one of the all-time favourites of illustrated books: “Alice in Wonderland”. The original edition of Lewis Carroll’s 1865 masterpiece featured 42 woodblock engravings by John Tenniel., which were created in close collaboration with the author. But Tenniel’s visions of the young heroine and her extraordinary encounters were only the first of many interpretations of Wonderland, ranging from 19th century Victorian conceptions of childhood to Walt Disney’s contemporary animated productions, where the use of primary colours and shortened narrative are designed to appeal to the youngest viewers. The two images below, drawn from Alice in the ‘Garden of Talking Flowers’, are a good example of the way in which time and cultural change influence the illustration of texts, even such iconic ones as ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and ‘Through the Looking Glass’:

Alice in the Garden of Live Flowers (1. Tenniel, 2. Disney Productions)_

Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland are very much products of their period; both the text and the illustrations are typically Victorian. As Humphrey Carpenter comments, Tenniel’s classical draughtsmanship matches Carroll’s carefully structured story, “One aspect of Tenniel’s formality has to do with the composition of his designs, which often echo the structure of the stories by means of a symmetrical, enclosing sense of balance. This is often achieved by the placing of Alice between two other characters: the Mock Turtle and the Gryphon, Tweedledum and Tweedledee in their armour, the Red and White Queens, and the Lion and the Unicorn”. 1 This is, then, an artistic choice of Tenniel, who frequently used ‘bordering techniques’ in his works in general.

But it is not only the structuring of the stories which are markedly Victorian; each story is set within the framework of a dream fantasy, which play into the interests of the Victorian imagination: medievalism, the grotesque, the supernatural, the gothic. All of these elements are clearly reflected in Tenniel’s designs.

‘Each generation gets, not only the government, but the Alice it deserves.’ (Malcolm Muggeridge)

Since these early years there has been a steady flow of illustrated editions, every set of designs adding to an increasingly complex and varied Alice iconography. As some of these designs show, the ‘real’ human figure of Alice changes, sometimes quite markedly, with the fashions and tastes of the time, while the more imaginary characters remain basically the same. A twentieth-century Punch editor, Malcolm Muggeridge, in his Foreword to the Peake edition, identifies this process as a specifically historical phenomenon: “Great masterpieces like Alice … need to be constantly re-illustrated to relate them to our changing circumstances. Each generation gets, not only the government, but the … Alice it deserves. Thus Tenniel’s Alice is as self-assured, even as arrogant, as Queen Victoria, whereas Mr. Peake’s is a bit of a dead-end kid.”2

In the case of Peake, his dark images of Alice were inspired by to the devastation caused by war (a response to the horrors of WW2 that were recently found in private letters):

Rough drawing of Queen of Hearts from Alice in Wonderland, 1945, by Mervyn Peake (in the British Library)

The creation of such a dark and demonic queen is markedly different from the dominant queen of Tenniel’s original drawings and the light, child-friendly version created by Disney.

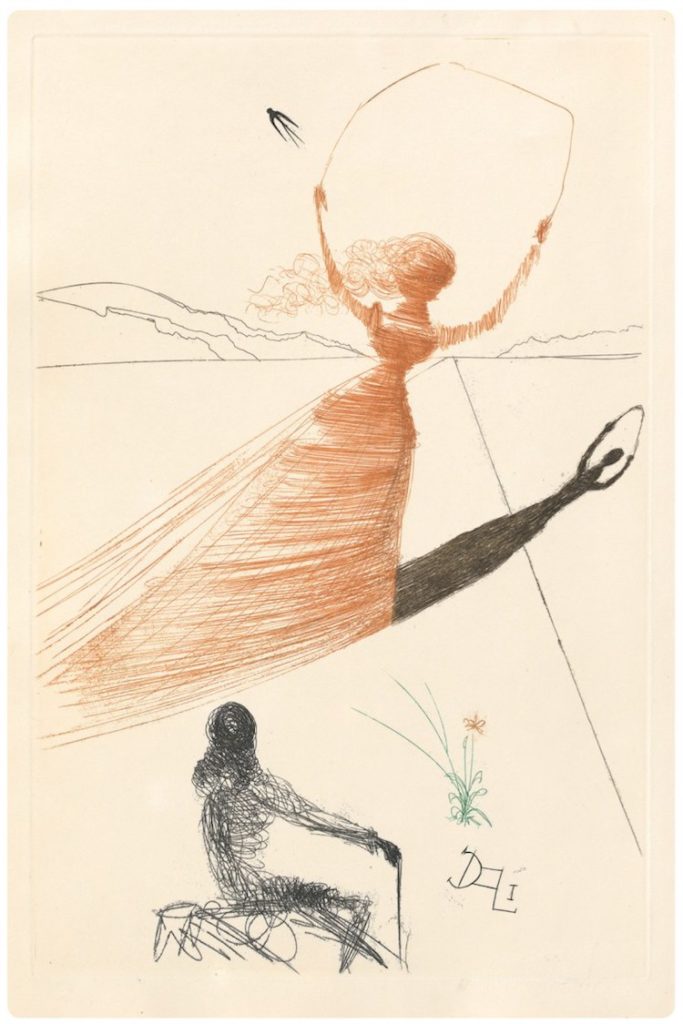

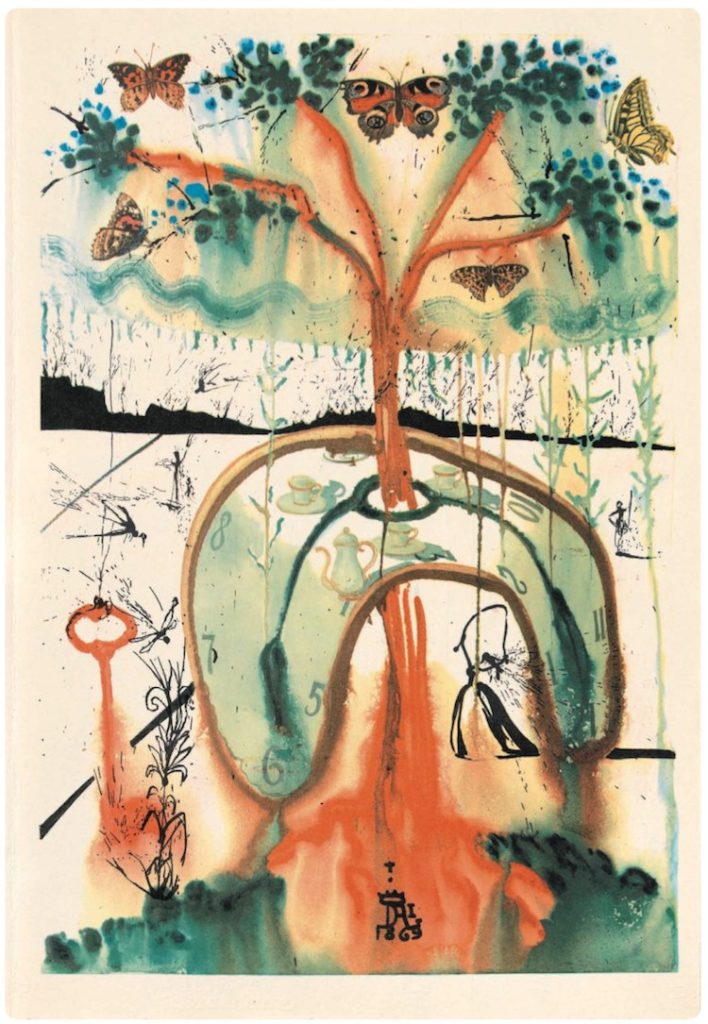

One more illustration of Alice in Wonderland gives an excellent example of an artist’s interpretation of a text that follows a particular art movement and the principles that generated it. Salvador Dalí created twelve heliogravures for the occasion—one illustration for each chapter—as well as a four-color etching as the frontispiece. “Those with a keen eye will immediately pick out some of Dalí’s signature imagery woven into the illustrations. The girl jumping rope in the frontispiece comes from his Landscape with Girl Skipping Rope and the iconic melting clock from The Persistence of Memory finds a nice home at the center of the Mad Hatter’s tea party”.3

First Published by New York’s Maecenas Press-Random House in 1969.

So what IS ‘Illustration’?

When someone says to us ‘let me illustrate’, we expect to hear an example, or an explanation. But in practice, illustration does not necessarily faithfully represent texts any more than ekphrastic texts faithfully represent artworks. Most of the going definitions of illustration suggest that the translation of the verbal to a visual (for example, poem to painting) calls for some truth to the original text. But as we have seen with our examples from “Alice in Wonderland”, every period seems to produce its own ‘take’ on the book, offering interpretations that often go outside its original sense.

Meyer Schapiro has suggested a variety of ways in which illustrations engage their visual sources, ranging from those that ‘enlarge’ the verbal text, adding details, figures, settings, and so on, that are not present in the original, to those which are extreme reductions of the text in which only a few details are represented. These artistic choices are often the function of cultural, social, and/or aesthetic concerns of a particular time and place, or reflect individual artistic style or ideology. As you already know, this same operation applies equally to translation between verbal and visual ‘texts’. I have often referred to this as a kind of ‘reverse ekphrasis’, but, in fact, I think that the two media actually translate from one to the other is such similar ways, that ‘reverse’ doesn’t really describe what is happening. Perhaps a better understanding for illustration (as I have suggested elsewhere 4) might be as a kind ‘pictorial ekphrasis’ .. not that it’s a term that we will use, but it might be a helpful way to think about illustration in the upcoming blog entries in Part 2.

In Chapter 1, Part 2, we will consider the relationship between the Pre-Raphaelite artists and Alfred Lord Tennyson’s ‘Lady of Shalott.

We will continue with this theme in September. In the meantime, see my latest posting on “Summer”!

- Quoted in Jill Stoker, “Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass”, reprinted in Alice in Wonderland Net, (www.alice-in-wonderland.net/resources).

- www.theguardian.com/books/2010

- Jessica Stewart, “Salvador Dalí’s Rarely Seen ‘Alice in Wonderland’ Illustrations Are Finally Reissued”: https://mymodernmet.com/salvador-dali-alice-in-wonderland/July 31, 2017

- Beyond Definition: A Pragmatic Approach to Intermediality, inMedia Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality pp 150-162 (Internet link: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9780230275201)