Just as artists/illustrators determine which perspective best fits their interpretation of a text – as we saw in the various illustrations of Judith and Holorfenes – so can poets take individual perspectives in regard to artworks. Below are a number of categories suggested by Gisbert Kranz (Das Bildgedicht, 1975) which are useful in identifying the varieties of ‘inroads’ into paintings taken by poets.

Varieties of Ekphrastic Perspectives (G. Kranz)

1. Rhetorical: the picture becomes a point of discussion. This can take a number of forms:

a. The figure in the picture addresses the viewer.

b. The figures in the picture or the viewers of the picture address each other.

c. The poet addresses the viewer/viewers.

d. The poet address a figure or figures in the painting, the painting itself, or the painter.

2. Descriptive: the picture is described in some way.

3. Meditative: the picture inspires reflection on the part of the poet/speaker.

4. Associative: the picture is associated with a personal experience of the poet/speaker

5. Panegyric: the picture, a person represented in the painting, or the artist is praised.

6. Pejorative: the painting, a person represented in the painting, or the artist is criticized by the poet.

These categories are simple guidelines; it goes without saying that an ekphrastic poem can take more than one kind of approach to its subject. Keats’ ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, for example, assumes most of the above stances: it is rhetorical because it addresses the object itself, it is highly descriptive of the images emblazoned on the urn , it is meditative in its consideration of the nature of art, and it is largely a panegyric (in spite of its debate concerning the frustrating silence of the artwork , which might be considered perjorative)

There are two other categories that Kranz mentions in his list of perspectives but that we don’t find in Keats’ ode: the Associative, a very personal engagement with the artwork.

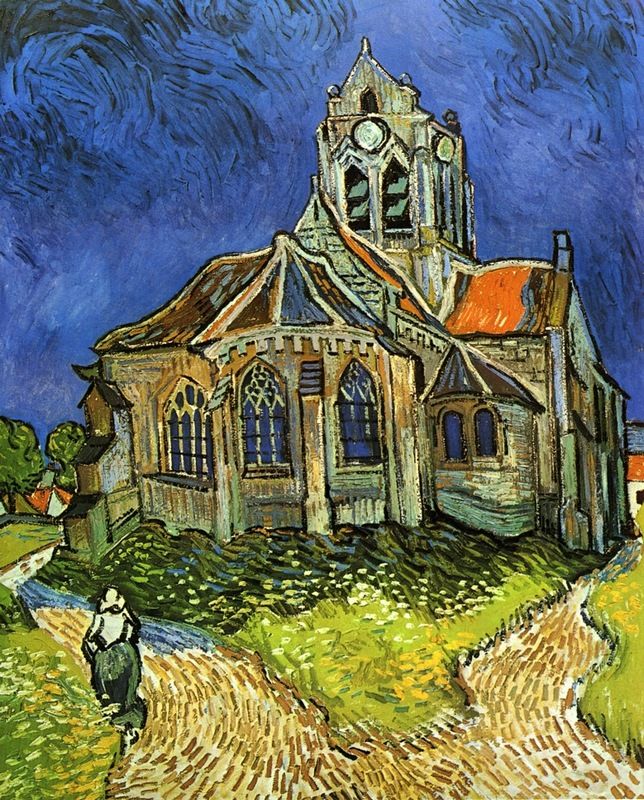

For an example of this, let’s have a look at Elizabeth Jennings’ poem ‘The Nature of Prayer’, which is based Van Gogh’s painting The Church at Auvers. As you will see, this poem, though inspired by the painting, has very little to do with the painting at all.

Vincent Van Gogh, Church at Auvers, 1890, Musee d’Orsay, Paris

The Nature of Prayer

(a debt to Van Gogh’s Crooked Church)

Maybe a mad fit made you set it there

Askew, bent to the wind, the blue-print gone

Awry, or did it? Isn’t every prayer

We say oblique, unsure, seldom a simple one,

Shaken as your stone tightening in the air?

Decorum smiles a little. Columns, domes

Are sights, are aspirations. We can’t dwell

For long among such loftiness. Our homes

Of prayer are shaky and, yes, parts of Hell

Fragment the depths from which the great cry comes.

Elizabeth Jennings, Selected Poems

(Manchester, UK: Carcanet Press, 1986), p. 119.

As you can see, Jennings’ poem is not ‘about’ Van Gogh’s painting at all. Although it is based on the painting, the only clue leading us to The Church at Auvers is in the sub-title. ‘The Nature of Prayer’, is a meditative poem on the experience of spirituality. As such, the poet has taken a rhetorical stance to the painting, questioning the artist himself on the reason for representing a church in such disarray. From here on, the poem develops this idea, becoming highly associative, as it focusses inwards to the speaker’s personal concerns about the stability of spiritual life and the incongruence of spirituality with the lovely and ‘lofty’ churches of her experience.

Let’s move on to Pejorative category, which renders a sustained critique of an artist or artwork. I think that it’s fair to say that these kind of ekphrastic responses are a bit thin on the ground – after all, most poets are nice people. One day, during a visit to the Hague’s Mesdag Museum to see the famous Mesdag Panorama (1880), I stepped over to the ‘dark side’ and determined to explore the pejorative approach myself (in solidarity with my students, who were asked by my colleague and myself to put their new-found knowledge of the principles of ekphrasis into an original poem).

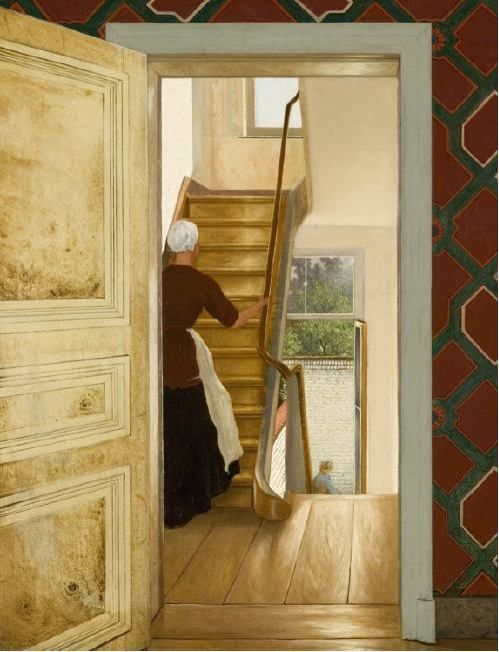

Let me explain: to view the Panorama, one stands on a ‘beach platform’, surrounded by a 360 -degree scene depicted on a canvas: a huge expanse of sea with boats in the distance, endless horizons, fishermen on the shore, women repairing nets, children playing in the sand, and a village just beyond the dunes. By contrast, I discovered, in a small room next to the Panorama, a painting by Mesdag, titled “Interior with Staircase” and I was struck by how starkly different this painting’s confining interior was to Mesdag’s generous landscape. This led me to pen a perjorative response and below is my contribution (with apologies). I include it here only to serve as example:

‘Interior with Staircase’

(To H.W. Mesdag)

In Mesdag’s great panorama

the ‘triumph of perspective’ tricks the eye

to see fishing boats, women repairing nets,

calming dunes, sunlight in shifting patterns on the sand.

We are enfolded into this scene,

its truthful image of village life.

But half-hidden in the ante-room beyond,

a painted maid, her back to us, ascends the stairs:

a seamless blending with the stark interior.

Everything turns away or blocks our view.

The door that opens to where we stand

does not invite us in to this desert of a house.

There is no glimpse of real life

that must take place here:

no pots or writing desks,

no jugs or clavichords alight with sun,

no tables set, no sullen maids or lazy dogs.

Half a servant mounts a stair; the rest is lost.

Mesdag, ‘master of realism’,

on completing your grand vista

were there no colors left

to paint the trappings of a family home?

Was your pen too dulled to sketch

the panorama of our daily lives?

Aside from being pejorative, the poem is also descriptive (of both the Panorama and the Interior with Staircase). It is also rhetorical in its address to the artist himself and the questions it poses to him. But the poem does something that is not covered by Kranz’ categories: it is what Hans Lund calls a ‘spatial contextual ekphrasis’, which means that it considers the painting in the context and space of its display: ie, next-door to the huge panorama. Further, the poem places ‘Staircase’ in the context of the Dutch Golden Age paintings, emphasizing the warmth of their family scenes and domestic interiors and beauty of everyday objects. This is what Lund calls a ‘temporal contextual ekphrasis’.* By inserting these other paintings into the poem by reference, a comparison is set up between the starkness of Mesdag’s interior and the rich tones and lively settings that we have come to expect from Dutch artists. I should add that someone else might write a panegyric to this painting, praising it for its honesty in depicting the ‘truth’ of the calvinistic and patriarchal confinement of domestic life. Again, it’s all about perspective!

The following posting (It’s All About Perspective II), will go more deeply into the various ways in which poets depict the visual arts.

* Hans Lund, “Ekphrastic Linkage and Contextual Ekphrasis in Pictures Into Words: Theoretical and Descriptive Approaches to Ekphrasis, Valerie Robillard and Els Jongeneel, eds (Amsterdam: VU University Press), 1998, pp. 173-188.