Let me introduce you to the ancient and well-fought ‘battle of the arts’. In our age of popular culture and an increasing trend toward ‘interdisciplinarity’, the very idea of a ‘struggle’ between art forms might seem silly and irrelevant. But it has been a serious topic that was central to discussions about the nature of the human senses, and the part that the arts played in our understanding of the world. Indeed, philosophers, artists and poets have had plenty to say about the subject over the centuries and volumes have been written on aesthetics and the philosophy of art. so you can understand that the subject is much too large to be responsibly addressed in a blog. Nevertheless, it would be good to have a very brief look at a couple of important contenders in the battle, to give an idea of the issues involved.

To our modern sensibilities, art and poetry would seem to belong to a ‘higher’ sphere of human production – one that involves creativity and the imagination. But the arts haven’t always enjoyed their current position on this pedestal.

Plato, for example, didn’t think much of either of the arts, as they were both too far removed from the ‘real’ world, which consisted of perfect forms. In his famous allegory (in The Republic, 3rd century BC), Plato argues that Man dwells in a cave and sees only shadows of the real world. Therefore, the arts, which can represent only the perceived world, are thrice removed from reality: paintings/poems represent the visible world of experience – which itself is a representation of the true forms that lie outside the cave of human existence. (Interesting to note that the philosopher, in Plato’s view, does have access to that elusive world)

Horace, in Ars Poetica (19 BC), insisted that both arts were to be regarded seriously but each, in its own medium, must be equally truthful in the representation of the world: in other words, “ut pictura poesis” (as painting, so poetry). As Horace graphically argues:

“If a painter should wish to unite a horse’s neck to a human head, and spread a variety of plumage over limbs [of different animals] taken from every part [of nature], so that what is a beautiful woman in the upper part terminates unsightly in an ugly fish below; could you, my friends, refrain from laughter, were you admitted to such a sight Believe, ye Pisos, the book will be perfectly like such a picture, the ideas of which, like a sick man’s dreams, are all vain and fictitious: so that neither head nor foot can correspond to any one form. “Poets and painters [you will say] have ever had equal authority for attempting any thing.” We are conscious of this, and this privilege we demand and allow in turn: but not to such a degree, that the tame should associate with the savage; nor that serpents should be coupled with birds, lambs with tigers”.

(You can imagine what Horace would think of Surrealism, Cubism, all forms of abstraction … not to mention the strange and horrific creatures produced by Hieronymus Bosch!)

Moving on to the views of practicing artists:

Leonardo da Vinci, centuries later, took a (predictable) side in what he called the ‘paragone’, the battle between the arts. As Leonardo saw it, it all had to do with the superiority of certain senses: the eye is superior to the ear, and therefore, painting (which is more pleasing and immediate to the eye) is superior to poetry. In his Notebooks (1508), he argues:

“The eye, which is called the window of the soul, is the principal means by which the central sense can most completely and abundantly appreciate the infinite works of nature; and the ear is the second, which acquires dignity by hearing of the things the eye has seen. If you, historians, or poets, or mathematicians had not seen things with your eyes you could not report of them in writing. And if you, 0 poet, tell a story with your pen, the painter with his brush can tell it more easily, with simpler completeness and less tedious to be understood. And if you call painting dumb poetry, the painter may call poetry blind painting. Now which is the worse defect? to be blind or dumb? Though the poet is as free as the painter in the invention of his fictions they are not so satisfactory to men as paintings; for, though poetry is able to describe forms, actions and places in words, the painter deals with the actual similitude of the forms, in order to represent them. Now tell me which is the nearer to the actual man: the name of man or the image of the man. The name of man differs in different countries, but his form is never changed but by death.”

Of course, poets through the centuries have written pointed responses to this kind of challenge. One of the most notable of these was penned by the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in his “Defence of Poetry” (1821), in which he claimed that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”. This defence was written in response to a witty magazine article by his friend, Thomas Love Peacock, who poked fun at the principles and claims of poetry, saying that poetry had become irrelevant in the age of science and technology and that intelligent people should give up their literary pursuits and put their intelligence to good use. Shelley responded with: “Your anathemas against poetry itself excited me to a sacred rage. . . . I had the greatest possible desire to break a lance with you …”

In his “Defence”, Shelley insists that poetry is not just another ‘craft’, but that the true poet is a visionary, a prophet, whose art reveals the nature of the world. Reason is logical thought; imagination is perception. Beauty will be revealed by means of both reason and imagination and this is where humanity becomes civilized. Poetry is language, which is linked to order and harmony. This is why Shelley puts poetry at the top of both divine and organic processes; in its expression of eternal truths, the poem is the ‘very image of life expressed in its eternal truth …the creation of actions according to the unchangeable forms of human nature, as existing in the mind of the Creator” and that “poetry lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world.” (Take that, Plato!)

Finally, an important voice in the battle of the arts is that of the German philosopher G.E. Lessing, who was not interested in the various merits of each art, but argued the limits of their expressive possibilities. In his seminal work Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1812), Lessing argues against the popular tendency to take literally Horace’s ut pictura poesis (‘as painting, so poetry’), which had been misconstrued to mean that both media can express the same thing in the same ways. For Lessing, painting and poetry cannot do the same things, but each has its own character: painting is ‘spatial’ and poetry is ‘temporal’. In other words, an image in a painting can be viewed immediately within the space of the canvas but the same image in a poem must be revealed over time. Both have their advantages and their limitations: a poem can relate the story behind the image, but cannot reveal its essence all at once; a painting, on the other hand, can reveal an idea in a single image, but cannot tell a story. (This is the problem that we encountered in Homer’s Shield of Achilles: the impossibility of representing a field that had been ‘plowed three times’).

Painting’s side of the argument

So what can paintings do? Paintings can represent a narrative in a limited way, by choosing the most important part of that narrative, or the ‘pregnant moment’, as Lessing calls it. The artist’s choice of that moment is, of course, somewhat subjective and presumes the viewer’s pre-knowledge or imagination to fill in these gaps. Let’s have a look at two illustrations showing two different ‘pregnant moments’ in the story of “Judith and Holofernes”.

Judith and Holofernes

The story comes from the ‘deuterocanonical book’ of Judith (Apocrypha): Nebuchadnezzar, King of Nineveh, sent his general Holofernes to subdue the Jews in Bethulia; but they were already suffering from from hunger, had lost all hope, and were considering surrender. A beautiful widow, Judith, determined to save her people and, with her maidservant, went to the Assyrian camp, seduced Holofernes with her beauty, waited until he was drunk, then decapitated him with a sword. She returned triumphantly to her people, carrying the head in a basket as a trophy. The Jews regained their courage and drove the Assyrians from the land.

The following images demonstrate the varying approaches that artists have taken in their representation of this story. The Renaissance painter, Artemisia Gentileschi, produced several of these, each taking different stances on the narrative. Only one will be discussed here: “Judith and her Maidservant”:

- Artemisia Gentileschi, “Judith and her Maidservant” (1613-14)

This painting portrays the moment after Judith has beheaded Holofernes and dropped his head in a basket. This ‘frozen moment’ is filled with tension and fear of discovery. Their gaze is focused outward – and out of the painting – and appear united in their fear. On her sword is emblazoned a gorgon, a symbol of power of the abused woman. This is a significant addition by the artist, as Gentileschi, had been raped by her tutor Agostino at the age of 18. The trauma from this abuse influenced her two depictions of Judith. For example, Judith’s face resembles the face of her abuser and she points this out in one of her notes on the painting: “I couldn’t make the greenish grayface look like anything other than Agostino’s. That bothered me. I didn’t want to paint out of hate (in Susan Vreeland, The Passion of Gentileschi, Chapter 14).

A later painting by Gentileschi (below) is far more violent and the face of Judith more determined and aggressive. A fine comparison between this painting and Caravaggio’s Judith has been offered by Dr. Esperanca Camara (www.kahnacademy.org).

“Judith Slaying Holofernes”, Gentileschi (1624-20)

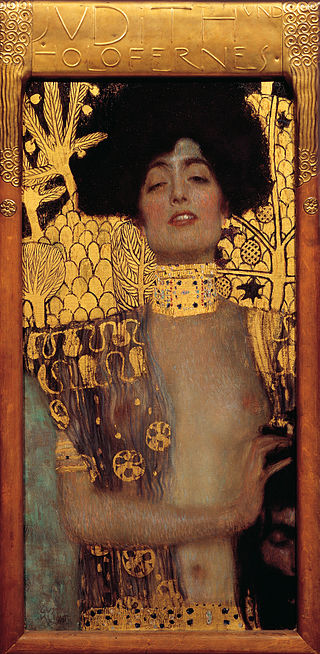

2. The following image is Gustav Klimt’s “Judith and the Head of Holofernes” (1901). As you can see, Klimt ( 1862- 1918), completely ignores the narrative of the story and focuses only on Judith (even Holofernes’ head is only partially visible in the bottom right-hand corner.) Instead, it is Judith herself who fills the entire canvas, her erotic gaze is directed back towards the viewer.

Why does Klimt do this? Recall that Klimt was painting at a time when the ‘femme fatale’ was a increasingly popular archetype for artists: a mysterious and seductive woman whose charms ensnare men and lead them to destruction. In Klimt’s Judith, we see pride and triumph in her victory over Holofernes. Even though Judith is portrayed in the Apocrypha as a simple, but beautiful, widow who kills Holofernes out of a sense of duty, her portrayal here is an artistic interpretation based on a tradition of the femme fatale – the female who triumphs over powerful men. It is also interesting to note that the erotic female figure was the primary subject of most of Klimt’s paintings, so it is clear that aesthetic milieu and artistic style determined his painting of Judith, and not the pregnant moment of the narrative. If one looks at the painting without knowing its association with the story of Judith, it would be easy to assume that this is another (beautiful) painting of a femme fatale of the time – perhaps even of Solome, who was an even more popular subject for painters than Judith. (Klimt, however, made certain that there was no mistaking in his subject for Solome: notice the inscription at the top of the painting).

So it is clear that painters and poets have certain restrictions in their modes of expression, but have a great amount of freedom in their approach to any topic (perhaps stepping on Horace’s toes in the process). In the following entry, I will discuss the iconic poem which ‘elaborates’ on the limits of painting and poetry: Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn”.