Well, I’ve done it again: I’ve used the term ‘ekphrasis’ in a title, knowing full well that this word can mean the kiss-of-death in any discussion or social interaction. Picture yourself at a busy cocktail party, for example, where attention spans usually run about 3 minutes, and someone asks you to explain ‘ekphrasis’ (yes, it really happens). By the time your three minutes are over, and you are just getting warmed up, you notice your companion’s eyes searching for the door. This brings me to my use of the title: “Ekphrasis for People in a Hurry”, which I borrowed from Neal de Grasse Tysons “Astrophysics for People in a Hurry”, where, according to one book review “Tyson brings the universe down to Earth succinctly and clearly, with sparkling wit, in digestible chapters consumable any time and anywhere in the busy day …for people who have little time to contemplate the Cosmos”. Admittedly, ekphrasis is not astrophysics, but it is a fairly complex system of relationships and has proven nearly impossible to explain ‘in 10 words or less’.

We will not be contemplating black holes, asteroids, or other workings of the cosmos here, but will explore a wide variety of relationship between literature and the visual arts that often shed light on cultural and historical norms and historical events, moments in time when the arts work together to make sense of their time and place. This is why the topic needs a better public platform – one that reaches beyond the halls of the academies, where it still largely resides. The interesting fact about ekphrasis is that it’s everywhere to be found, once you know where – and how – to look.

Let’s start with a definition of our topic: ekphrasis. This term simply refers to the representation of existing or imagined works of art in poetry, prose, and drama. That’s it! But beware: ekphrasis is often confused with pictorialism, where a poem vividly describes a scene or object as if it were a painting. That’s how all good poems use imagery. But ekphrastic texts are always related in some way to existing artworks or ones that have been invented (often called ‘fictional’ or ‘notional’ ). In other words, a poem about a tree is not ekphrastic; a poem about a painting of the same tree is ekphrastic.

In sum: There are two major types of ekphrasis: Actual and fictional (or notional) ekphrasis. Actual ekphrasis is a literary work that is based on a real or existing work of art; notional ekphrasis is a literary work that is based on a fictional work of art.

A good example of notional ekphrasis is Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’. The work of art that drives the narrative of the poem is not really the subject at all, but is there to illuminate the cruelty of a proud Duke within a patriarchal society. This poem is a dramatic monologue, wherein the duke addresses an emissary who has come to arrange his next marriage. He speaks to him about his dead wife, the “last duchess” of the title, through the medium of a portrait of her that is hidden behind a curtain. The duke pulls the curtain to reveal the painting and asks the emissary to contemplate it while he relates the ‘flaws’ and fate of his late duchess, soon to be replaced by another.

Here are the first 5 lines of the poem, which focus briefly on the subject, the painting, and its maker:

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Fra Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her?

The remainder of the poem focuses on the young Duchess herself and the wilful flirtations that aggravated her husband, the Duke, to such an extent that he ‘…gave commands/and all smiles stopped together.’ She is present only in her painted image. where ‘she stands/as if alive …’ . The work of art here is employed ekphrastically to reveal the violence that underlies the ‘frozen image’ of the young duchess.

There is much more to be said about the poem, but for now let’s move directly on to ‘actual ekphrasis’.

Actual ekphrasis: To illustrate the difference between notional and actual ekphrasis, let’s have a brief look at the following poem by Elizabeth Jennings, which is based on a real/actual artwork, one of Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. The entire poem is addressed to ‘you’, the artist Rembrandt, and his uncompromising depiction of ageing. Here are the first 6 lines:

‘Rembrandt’s Late Self-Portraits’

You are confronted with yourself.

Each year

The pouches fill, the skin is uglier.

You give it all unflinchingly. You stare

Into yourself, beyond. Your brush’s care

Runs with self-knowledge. Here

Is a humility at one with craft.

By naming the artist and artwork in the title and using description throughout, we know that we are encountering an actual ekphrasis: we recognize the name of Rembrandt and may know that he executed a series of self-portraits from his youth to old age.

Both poems use paintings (real or fictional) in some way: one to make a comment on a particular society, the other to the praise the painter’s art and his common humanity as expressed on the canvas. Indeed, there are many ways that poets and writers approach works of arts; one might look at ekphrasis as a type of ‘interpretation’, a way of giving new meaning that relies on factors that go beyond the text or artwork; indeed, ekphrastic texts reveal much about the time and place in which they were written and the cultural/aesthetic milieu that generated them. As Bram Dijkstra explains:

The real developments, the innovations, in art and life, whether in literature or painting, depend on the manner in which the elements of one medium are translated to the condition of another.

It was this notion of ‘real developments’ in the arts being viewed through ‘translation’ of one medium to the other that set me on my long journey through the complex world of ekphrasis.

The Journey

It started with an exhibition of the collected works of Kasimir Malevich in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. What struck me most as I moved from room to room (where the paintings were chronologically organized) was that, in this astonishingly diverse one-man-show, I was witnessing the very development of modern art. It also occurred to me at the time that Malevich’s inclusive embrace of various emerging art styles within modernism had much in common with the work of modernist poets, notably that of Williams Carlos Williams, whose close involvement with the visual arts resulted in rich ekphrastic poetry that represent many attempts to break through the boundaries of his own verbal medium to represent these various art styles in his poems. Indeed, as we move (so to speak) from poem to poem, we find many modernist styles reflected there, and the sheer variety of these texts suggests that Williams, the poet, was exploring his aesthetic milieu with the same intensity that Malevich, the artist, explored his. Although one of the most notable of ‘ekphrastic poets’, Williams was by no means alone in this poetic pursuit of the visual arts; indeed, he belonged to a very rich tradition that we have witnessed through the ages, one that began when primitive peoples combined art, music, and dance in ceremonies meant to please the gods and ensure a good harvest. So much has happened to the arts and their liaisons in the intervening centuries and I hope that our present study will be a fascinating journey.

Trust me, I’m an ekphrasist…

Why Ekphrasis?

Although there are varieties of ways in which the visual arts interact, I am beginning our journey into Word and Image by dedicating Part I entirely to ekphrasis. As I stated in the general introduction, ekphrasis is an important, and yet one of the most neglected, tropes (type of literary response), in literary criticism. Even the word itself evokes puzzled looks!

To better understand ‘ekphrasis’, it’s helpful to consider the term in its historical context. As it’s now defined, ekphrasis refers to the manner in which literary works of art describe or evoke existing or imagined works of visual art. The term is part of a tradition which hails back to the Greek schools in the third to fifth centuries where young scholars were trained to be orators and teachers of rhetoric. In this context, ekphrasis (which originates from the Greek ekphrazein, ‘to describe exhaustively’) was an exercise in describing objects or scenes as vividly as possible in order to bring these ‘before the eye’ of the listener, or, in other words, to create mental images.

With the change from the oral to the written word, however, ekphrasis developed into a popular mode of expression among writers, but its use has evolved from the description of anything to descriptions of works of visual art. This can be seen early on, in one of our first recorded ekphrastic texts: Homer’s description of the making of the shield of Achilles in Book 18 of the Iliad. Homer begins his ekphrasis with the construction of the shield:

“And first Hephaestus makes a great and massive shield, blazoning well-wrought emblems all across its surface, raising a rim around it, glittering, triple-ply with a silver shield-strap run from edge to edge and five layers of metal to build the shield itself.”

Homer then moves on to Hephaestus’ creation of the images on the shield, where he hammers the shield into five sections and covers them with images of the earth, sky, sea, sun, moon, and constellations, two cities, a wedding celebration and a court case, a city under attack, an ambush and a battle, wild beasts, a war, a field full of plowmen, a vineyard, a meadow, and dancing boys and girls, the great stream of ocean.

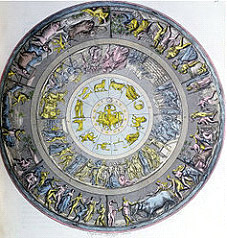

It seems that Homer has provided his reader with an impossible number of images to be engraved on an ordinary shield, yet many artists have successfully attempted to reproduce this fictional artwork. Below is just one of these (Angelo Monticelli, 1820).

This reproduction (or ‘illustration’) of the shield by Monticelli remains as close as possible to the original text, with some interesting exceptions, for example the representation of a field being ‘plowed for the third time’. Here we encounter the problem of ‘words versus images’, which is the subject of the next chapter.

As opposed to Monticelli’s sculptural response to Homer’s description, W.H. Auden’s famous poem ‘The Shield of Achilles’ does not intend to represent the shield as Homer presents it, but rather casts it in an entirely new light. Here are the first two stanzas.

The Shield of Achilles

She looked over his shoulder

For vines and olive trees,

Marble well-governed cities

And ships upon untamed seas,

But there on the shining metal

His hands had put instead

An artificial wilderness

And a sky like lead.

A plain without a feature, bare and brown,

No blade of grass, no sign of neighborhood,

Nothing to eat and nowhere to sit down,

Yet, congregated on its blankness, stood

An unintelligible multitude,

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign…

For the full text and a brief, but excellent, discussion of this poem, have a look at the Circe Institute’s website.

In Auden’s recasting of Homer’s text, Thetis looks over the shoulder of Hephaestus, expecting to find the same scenes of hope and plentitude depicted on the shield; instead, she sees only the barren and hopeless landscape of the modern world. (One could argue that Auden has also been true to Homer’s text in noting all of the images that should have been there but are now absent.)

Both artistic responses have attempted to translate a (fictional) work of art embedded in a poem into their own medium: one is a visual artwork, the other is another verbal artwork, or poem. Both of these responses challenge our definition of ekphrasis…. but that’s the excitement of a term like ekphrasis. By encountering a variety of ekphrastic responses, we learn very quickly that artists and writers continue to experiment in new ways that defy or outrun our attempts to classify them … or, as the critic Murray Krieger has put it, ‘to wrestle ekphrasis to the ground’.

Take heart! The next chapter we will look more closely at these challenging questions!