Three baseball umpires were asked to explain the basis on which they made their ‘calls’. The first umpire said: “Well, there are ‘balls’ and there are ‘strikes’ and I call them as they are”. The second umpire responded, “There are ‘balls and there are ‘strikes’ and I call them as I see them.” The third umpire was silent for a moment and then said, “There are ‘balls’ and there are ‘strikes’ – but they ain’t nothing until I call them”. (A story going the rounds)

Pinning down or ‘naming’ experience is all down to perspective. Labels and terms are often subjective, as they are based on social, cultural, or experiential factors. Consider the change in the meaning and use of the term ekphrasis over the past centuries (see Chapter 1). Labels may seem unreliable precisely because of their subjectivity, but like them or not, we need them. We need to know what people around us are talking about; we need terms that are understood and agreed upon by any group of people at any given time. We need to agree, in other words, on how to make our ‘calls’.

To complicate matters, terms are notoriously fluid, subject to constant changes in our world. Think about the word ‘mall’, for example. If someone says that she is going to ‘the mall’, most people in any American city would understand that she plans to go to a shopping at a commercial center with many stores under one roof. But if she were to announce her plans to a contemporary in 1737, it would be assumed that she planned to amble in “a broad, tree-lined promenade similar to the one in St. James’s Park, London, so called because it formerly was an open alley that was used to play pall-mall, a croquet-like game involving hitting a ball through a series of rings’ (www.etymonline.com).

So far, we have looked at a small number of ways in which poets translate a work of art into their own medium. These ‘re-workings’ are essentially translations and translations is always subject to perspective of the translator, even when staying as true to the original as possible (recall Williams’ exclusions (magpies) and inclusions (enlargement of inn sign), which have interpretive consequences of their own: why did Williams omit magpies, which. are everywhere important in Brueghel’s works? Why enlarge a sign that is given a rather insignificant place in the painting? These are interpretive choices (and ones that have been often discussed in relation to Williams’ poetry. I will post some references to these later on).

An Ekphrastic Roadmap

I think that it has become clear that poets follow many roads into paintings and these paintings can be ‘recast’ in a variety of ways. One confusing aspect of a term like ‘ekphrasis’ is that it includes every type of poetic response to paintings under one umbrella term. Ask yourself this: how much of a painting needs to be represented in a poem to be called ‘ekphrastic’? Is description of a painting more ‘ekphrastic’ than simply naming the artist/painting and moving on to one’s own personal reflections (recall Jennings’ poem on Van Gogh’s crooked church)? Can a poem simply name a painting, without any other reference to it ,and still by called ‘ekphrastic’? What if the poet makes only an allusion to the paintings of an artist or the type of paintings in that same genre? Is that ekphrastic? What if there is no direct ‘naming’ at all, but only a few small clues in the poem that will be picked up only by readers familiar with the art style or artist?

This is the problem with terminology: it’s both useful and limiting. Remember from the first chapter titled ‘Why Ekphrasis’, that the original idea of the term was to bring the image before the ‘mental eye’ of the listener/reader. In this case, we can assume that poets will mark their ekphrastic poems with something – either direct or discrete – to bring that image to mind. A (nearly) complete description of a painting (as in Williams’ ‘Hunters in the Snow’) will bring the picture to mind for most people; on the other hand, a poem that refers simply to ‘diagonals and hunters’, with no other mention of artist or painting, will relay Brueghel’s Hunters in the Snow to only those who are familiar with his work.

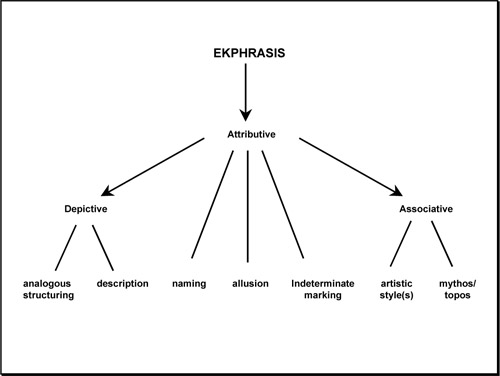

One of the focus points of my own research has been to create a useful roadmap to help identify these various types of ekphrasis as ‘subsets’. If you like typologies as much as I do, then welcome to my Differential Model: a graphic way of laying out the types and intensity of ekphrastic reference.

To reflect these differences, I have constructed a typology, which I call ‘The Differential Model’ (first published in Pictures into Words, 1998). This model is organized in a left-to-right configuration to illustrate the depreciating strength of ekphrastic relationships, both in the main categories as well as in their sub-categories. For example, a poem that is depictive (ie, describes elements of the painting) will have a stronger ‘ekphrastic impact’ on the reader than a poem that is mostly associative (ie, one that is more concerned with wider meanings or associations evoked by the painting). For example, think of Jenning’s poem on Van Goghs ‘crooked church’ (see Chapter 4). A poem that directly names a painting will have a stronger impact on the most readers than one that merely gives a clue it’s source.

The Differential Model

(Robillard)

Attributive category

Ekphrastic texts are usually attributive, ie, mark their source paintings in some way. Attribution takes more than one form; in the model, this is accounted for by sub-categories, which are organized according to their ‘intensity’, ie, to how clearly the artwork is marked in the text. This happens in three ways: 1) naming the source, either in the title or in the text, which establishes the strongest link to the painting; 2) alluding to the painting, painter, style, or genre; 3) indeterminate marking, which are clues planted in the text which the reader must recognize as referring to a specific artwork or some aspect of it. I have placed this furthest to the right in the typology, as it is the weakest form of marking: only readers who are familiar with the artist, paintings, or genre would be likely to pick up the clues.

Depictive category

This category identifies texts which bring some material aspect of the painting into the poem by imitating or describing these in some way. The sub-category, analogous structuring, refers to the writer’s attempt to imitate the visual impact of the painting (remember Williams’ use of diagonals and saccades in ‘Hunters in the Snow’). The sub-category, description, is a bit weaker than the first, because the amount of description may vary from a faithful mention of most or the details of the painting to the mention of just one of these.

Associative category

This category accounts for references made by the poet to some more general aspects of the artwork(s) referred to in the text. The first sub-category, artistic styles, which I have placed to the left because it refers to the materiality of the artwork, accounts for poems which make general references to the artistic styles of one or more artists. The second sub-category, mythos/topos is less ‘intensely’ ekphrastic in the sense that it extends beyond the artwork itself and considers themes or conventions/ ideas associated with it or with the arts in general . (Think of Auden’s line in “Musee des Beaux Arts” , ‘About suffering, they were never wrong/the old Masters’ )

Considering Williams’ “Hunters in the Snow” in terms of these categories, it would be safe to say that this poem is strongly ekphrastic: it explicitly names the artwork directly in its title and the artist in the final lines (‘Brueghel the artist/ concerned with it all…’). As far as the depictive category is concerned, Williams imitates the organization of Brueghel’s painting by using saccades and diagonals (analogous structuring) and most details of the painting are described. The poem is not associative, as the focus of Williams’ ‘translation’ is on the materiality of Brueghel’s painting; it is, therefore, highly depictive and highly attributive.

We will make use of this road map as we go along to practice differentiating between the various types of ekphrasis in the poems that we encounter from now on. It should be clear by now that if we define a text as ‘ekphrastic’ based solely on its depictive qualities, then only those texts which are descriptions would qualify as ‘ekphrastic’. Yet there are many ways that a painting can be made visual to the reader and I hope that the ‘Differential Model’ will help you in identifying these. Perhaps you might even explore the varieties of ekphrasis by writing a poem about one of your favourite artworks!